Darling of the Gods

Jamie Barras

Butterflies

“It was the beginning of November 1903 when Mr. Spielmann told me that Sir Herbert Tree (Mr. Tree, then) was going to reproduce a Japanese play called “The Darling of the Gods” [and] I might be a useful help for him”

After New York impresario David Belasco scored a big hit bringing John Luther Long’s short story Madame Butterfly to the stage (six years before Puccini would turn the story into an opera), Belasco and Long conceived the idea of producing a second play on a Japanese theme using only Japanese characters. Although drawing on the same real-world events that would later inspire the movie The Last Samurai, the resulting play, The Darling of the Gods, was a po-faced pantomime complete with an evil vizier/war minister, a beautiful veiled princess guarded by a mute slave, and an outlaw who lived in the woods with his band of melancholy men. One London critic would go on to describe it as ‘gorgeous claptrap’. The only truly Japanese element of both the original 1902 New York production and the 1903 London transfer was the set and costume design. In the New York production, this was the work of illustrator Genjiro Yeto (江藤 源次郎, Etō Genjirō). In the London production, it was overseen by Yoshio Markino [2].

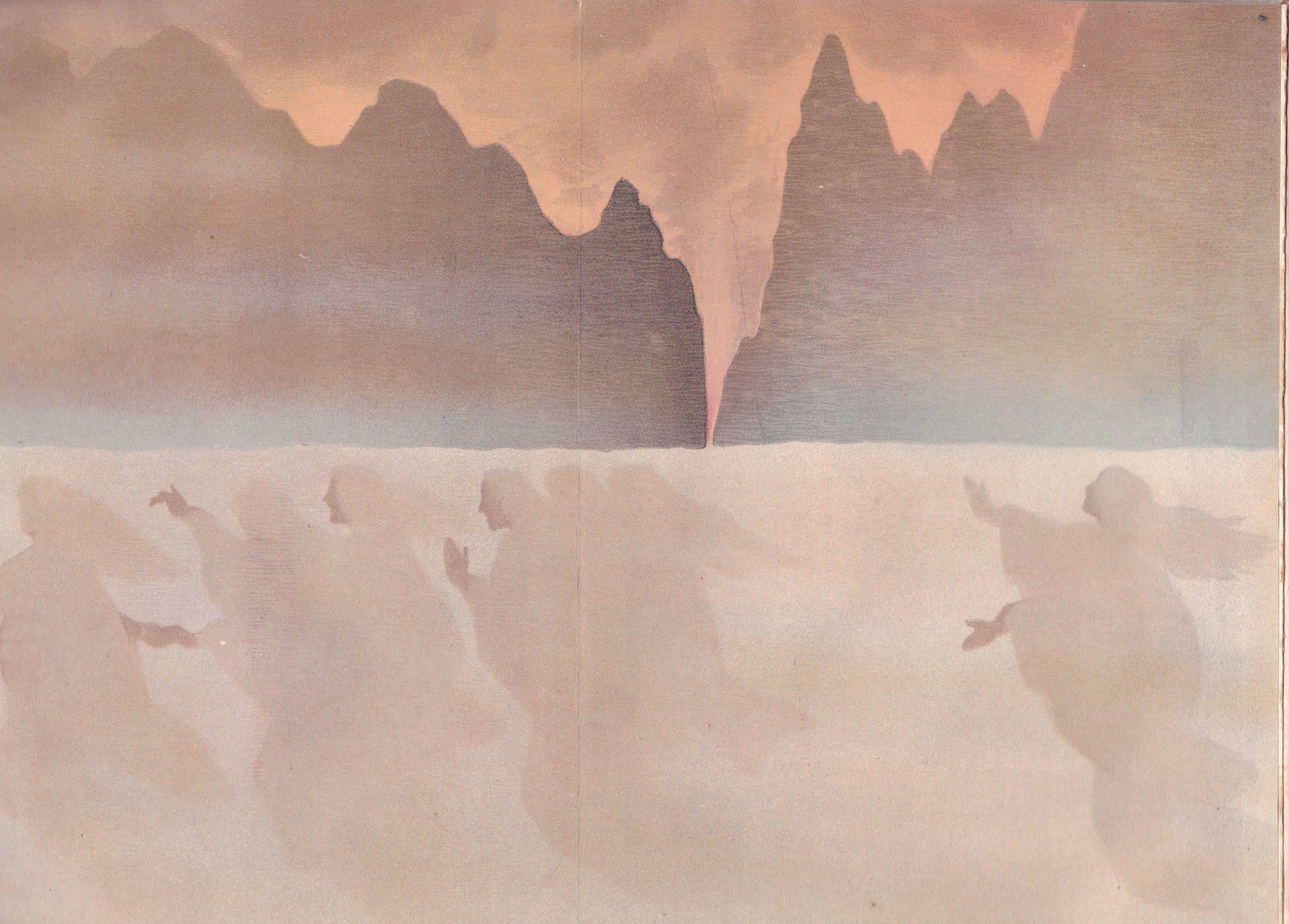

Detail, Yo-san dancing for her father, by Yoshio Markino, Darling of the Gods souvenir programme, 1904. Author’s own collection.

“Markino is perfectly full of such stories now laughable, then serious, all the same highly pleasing; oh, to spend half a day or one whole day if possible with him, and listen to his endless stories!”

Perhaps better than anyone else, artist and author Yoshio Markino (牧野 義雄, Makino Yoshio) can lay claim to having witnessed firsthand the rise and fall of the Japanese community in early 20th-century London. A puckish observer of both his fellow expatriates and his British hosts, Markino led a charmed but largely poverty-stricken life in England from 1897 until his repatriation to Japan on board El Nil in 1942 [4].

Yoshio Markino, frontispiece, When I was a Child (London: Constable & Company Limited, 1912). Public domain.

Born Heijiro Makino (牧野平治郎, Makino Heijirō) into an impoverished samurai family in 1869, his given name was changed to Yoshio on his adoption by Hanji Isogai (磯貝半治, Isogai Hanji), a distant relative; however, ‘Heiji’ would for the rest of his life remain the name by which he preferred to be called by his friends. The reasons for the adoption were financial, the idea being that Heiji/Yoshio’s adopted family would provide the money he would need to receive an education. Isogai was the first of many patrons to whom the cash-strapped Makino would be beholden. After a period spent working as a teacher, Makino left his homeland in his early 20s to travel to the USA, initially with the idea of studying English literature but finally, at the suggestion of another patron, settling on painting. This was the start of a peripatetic life that brought him, by chance, to London in 1897.

It was in London that Makino adopted a new spelling of his name, ‘Markino’, supposedly because it sounded more ‘ordinary’ to Western ears. After a period working as a clerk in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN)’s London office while studying art, he came to the notice of the editors of magazines like The Studio and The Magazine of Art. This started him on the road to success as an artist and writer in Edwardian London. His specialty in this period was washed-out watercolour paintings of London scenes, which gained him the soubriquet ‘Heiji of the London fog’ (ロンドン霧の平治, Londonkiri no Heiji). Markino loved the fog; to him, like the electric lights that shone dimly through it, it meant modernity. The London fogs cemented Markino’s decision to make the city his home.

By Yoshio Markino - A Japanese artist in London, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90785591

Although he chose to live mostly apart from the London Japanese community, he formed important friendships with the city’s Japanese visitors and residents; and while an ardent admirer of Western women, his closest friendships were with other men, notably poet Yone Noguchi (野口 米次郎, Noguchi Yonejirō), whom he had first met while living in the USA, and later, a young diplomat who would go on to become the ambassador of Japan in London at the time of the outbreak of the European War, Mamoru Shigemitsu (重光 葵, Shigemitsu Mamoru). The latter friendship would lead to Markino becoming a privileged witness to the community’s final years, as at the outbreak of the European War in 1939, Ambassador Shigemitsu would invite him to stay at the Japanese Embassy as a ‘resident guest’.

More than this, when Shigemitsu himself was recalled to Japan in 1941, he arranged a lifeline for Markino, a £300 line of credit at the London branch of the Yokohama Specie Bank (YSB) [5].

Shōkin

“[My father] always said, “ Children ought not to know too much about the money matters.” So, when I wanted some books, papers, etc., I used to go to shops with his servants. I picked up all what I wanted in the shops, and after I left the shops the servants used to pay. In that way I did not know the values of anything until I became fifteen or sixteen.”

The Yokohama Specie Bank (横浜正金銀行, Yokohama Shōkin Ginkō, aka Shōkin) was founded in 1880 and established its first branch in London within a year. As an exchange bank, its principal business was to facilitate international trade, acting as a middleman between Japanese firms and foreign companies that wished to buy Japanese goods. As Japan’s principal export for much of the late 19th and early 20th century was textiles, much of the YSB’s business was in facilitating this trade. Even as late as 1935, by which time Japan’s economy had started to diversify, the London branch of the YSB held UKP 30.6 million in import bills, one-third of which were for payment for textiles imported into the UK. As international trade was seen as vital to the expanding Japanese economy, and, by extension, expansionist ambitions of the Empire of Japan, the Japanese government took increasing control of the YSB’s activities from the late 19th Century onward, to the point that, particularly in Northern China, the YSB was regarded as synonymous with the Japanese state. This would prove to be to its detriment in the 1930s. This was particularly true in London, leading the YSB branch there to find it increasingly difficult to find buyers for the discounted bills that it offered for sale. Parallel to this, trade between the UK and Japan was also in decline, partly because of a boycott on Japanese goods triggered by the Rape of Nanjing in December 1936, but also because of an ongoing trade war between the British and Japanese empires over control of the sale of cotton to South-East Asia, which I cover elsewhere (see also below) [7].

YSB seal, cheque, 1907. Author’s own collection.

Control of the YSB’s London branch in this troubled period was in the hands of future Nile voyager, Hisaakira Kano (加納久朗, Kanō Hisaakira), known in England as Viscount Kano. Kano was born into a noble family, but despite his aristocratic upbringing, he would mature into a left-leaning Internationalist and pacifist under the influence of Christian teachings. While studying law at the University of Tokyo¬—where Mamoru Shigemitsu was a fellow student—he published a book critical of the Japanese government of the day (これからの日本, Korekara no Nippon, The Future of Japan), which was banned by the Censor. That same year, he married his first wife, a fellow devout Christian by the name of Tatsu Ito (伊藤多津, Ito Tatsu). The couple would go on to have five children together, the youngest of those, Rosa Hideko Kano (加納ローザ英子, Kano Rosa Hideko) [9], being born in 1921, during Kano’s first posting to the London branch of the YSB.

Hisaakira Kano by Bassano Ltd, whole-plate film negative, 12 March 1937, Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, NPG x152791 CC by-nc-nd/3.0

At first glance, Kano’s decision to go into banking after leaving university seems paradoxical given his politics, but it must be remembered that to Japanese men of his class and faith, expanding Japan’s contacts with the world through international trade seemed the best counter to the rampant nationalist militarism that was gripping the country. The fact that ultimately, the YSB would become a tool of the militarists that Kano so abhorred should not detract from that governing ideal.

In London, Kano began to explore fully the world of international socialism, joining the Fabian Society and giving speeches at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park. His commitment to those ideals would only deepen over the years. It was also at this time that he would, like Markino, become a confirmed anglophile. Where some saw diffidence and equivocation, Markino and Kano saw poise and moderation, qualities that, for very different reasons, perhaps, both men found infinitely more appealing than the extremes of emotion they had witnessed in the USA, Germany, and, yes, back home in Japan. Kano’s first posting in England was brief, ending in 1924 after only four years, but he and his wife and youngest daughter would return.

Interlude: Resilience, Love, and Sacrifice

Nineteen Twenty-Four was a big year in the life of two other future Nile voyagers with a YSB connection, as this was the year that Katsura Takashima (高島一貫, Takashima Katsura), a 30-year-old clerk at the London branch of the YSB, married 32-year-old milliner Hilda May Locke (高島ヘルダ・メイ, Takashima Helda May in Japanese sources). Alas, unlike Kano and Markino, information about the Takashimas is hard to come by. That Hilda May ultimately chose to return to Japan with her husband, despite England and Japan being at war by the time of their repatriation, speaks of a deep connection between the two, which was only severed when Katsura died, which happened sometime between 1942 and 1947 (probably but not definitely as a result of the war). At the same time, her decision to leave England behind may have been influenced by personal tragedy: at 25, she had given birth to an illegitimate child, a daughter, whom she had been forced to give up. The Takashimas’ story is one of resilience, love, and sacrifice, a small drama when set against the backdrop of world events, nevertheless, worthy of telling [10].

The Mysterious Affair at Paddington

“The highest peoples are very natural, because they have money enough, and they can do just as they like”

The 1920s were a period of change for Markino too. In 1921, despite once again, hovering on the edge of poverty, he was deemed of sufficient cultural significance to be invited to meet Crown Prince Hirohito—the future Shōwa Emperor—on the Prince’s tour of England. More significantly (or perhaps not—with Markino it is hard to tell), in 1923, he married. On the surface, this was a typical Markino story. His bride was a young impoverished Frenchwoman on whom he took pity. The pair remained married as long as it suited them both and then divorced on the grounds that the marriage was never consummated [12]. However, the full story appears to be much stranger.

Markino’s bride was 33-year-old aspiring actress Marie Eugenie Piron (マリ-・ビロン, Mari Biron in Japanese sources) and her marriage to Markino was her second. Her first marriage, in 1919, had made headline news in England. A year earlier, an English aristocrat, the 4th Earl of Craven, had started to receive first messages and then visits from a young man claiming to be his second son, Earle [sic] Uffington. However, the Earl of Craven did not have a second son—the man was an imposter. As much of a nuisance as the Earl of Craven found all of this, there was nothing he could do about it as the young man had committed no crime; until, that was, he married a woman whom he believed to be a 25-year-old war widow and lady’s maid by the name of Marie Eugenie Pardoe.

Headline, London Daily Chronicle, 4 April 1919. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

In falsely signing the register Earle Uffington, son of the 4th Earl of Craven, the young man had finally committed a crime that could get him arrested. This information was passed to the police and ‘Earle Uffington’ was arrested on his honeymoon. An Old Bailey trial ensued, during which it was revealed that the young man’s real identity was Carlo Mirelli, an Italian national raised by a foster family in the USA. A fantasist and possibly developmentally challenged, Mirelli had decided to assume the identity of a fictitious youngest son of the 4th Earl of Craven after seeing a photograph of the Earl’s actual son, Viscount Uffington, and deciding that he and the viscount bore a strong resemblance. It was also revealed during the proceedings that Mirelli’s bride, the woman he believed to be 25-year-old war widow Marie Eugenie Pardoe, was actually 28-year-old ‘spinster’ Marie Eugenie Piron—the same Marie Eugenie Piron who would marry Yoshio Markino four years later. Piron/Pardoe’s motives for moving into the same lodging house as Mirelli/Uffington, which is how their relationship began, went unexplored. Similarly, it went unreported that Piron/Pardoe was an aspiring actress. Carlo Mirelli was sentenced to 3 months in prison and then presumably (the press is silent on the matter), deported [13].

What are we to make of all this? At this distance, all that we can say is that it was incredibly convenient for the Earl of Craven that the man who was proving such a nuisance should decide to marry, and, in doing so, commit a crime that could get him arrested, and it was incredibly convenient that someone should inform the police of the fact; it was also very strange that the woman that this young man had decided to marry should prove not to be whom she said she was, and very strange that, despite this being the crime with which her husband was charged, she should escape prosecution.

Corrected marriage register entry for Earle Uffington/Carlo Mirelli and Marie Eugenie Pardoe/Marie Eugenie Piron, 1919. Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1938.

In a curious, but perhaps telling, sequel to this affair, a few months later, the Earl’s real son, Viscount Uffington, who was a war hero and amputee, was declared bankrupt, despite being the heir to both the family estate and a large fortune belonging to his American-born mother, Cornelia, Lady Craven (née Martin, a so-called ‘dollar princess’). His father had refused to settle his debts, most likely as a response to his secret marriage to a woman of humble origins a year earlier. The Earl was a man given to decisive, even extreme, action. In an even more curious sequel, he would, just two years later, die in mysterious circumstances, being found drowned after seemingly—there were no witnesses—falling overboard from his yacht late one evening.

How much of all this Markino knew when he married Marie Eugenie Piron two years after the death of the 4th Earl of Craven, I do not know. Given his love of the British aristocracy and storytelling, it is hard to believe he would not have written about it had he known. Regardless, it was in the aftermath of his brief marriage, that Markino became more or less completely reliant on the financial support of friends and visitors from Japan. At the same time, it is clear that there was no thought of him returning to Japan.

Intersection

“COLONEL THE MASTER OF SEMPILL, opening an exhibition of oil paintings entitled “Hyde Park in the Night,” by the Japanese artist, Yoshio Markino, at the New Studio Gallery, Knightsbridge, London, yesterday said that, while many English artists had borrowed inspiration from Japan, Mr Markino was one of the few Japanese artists to compliment England by obtaining inspiration from her.” ”

Markino celebrated the end of this most tumultuous of decades with another change of direction, abandoning painting in watercolours in favour of paintings in oils. In a speech he made in 1929 at his first exhibition of oil paintings, he gave some insight into his painting method, telling his audience that he carried a still camera with him when he was out and about and photographed, if he could, any scene that interested him. When he was not able to take a photograph, he would commit the scene to memory and while the impression was still fresh, head back to his studio, ‘close his eyes, and draw a rough outline on the canvas blindfolded’ [16]. His insistence on keeping a separate studio as well as his lodgings was one of the reasons that he was forever under financial strain.

He continued to exhibit from time to time in the new decade—a reviewer of an exhibition of his works at the Wertheim Gallery in Burlington Gardens in 1933 described his paintings as ‘Essentially graceful and tender paintings, they should have a wide appeal.’—however, mostly, he led a secluded life. His 1934 Who’s Who entry gave as his means of recreation: ‘Reading the Ancient Chinese, Latin, and Greek classics in order to forget the modern civilisation’ [17].

It is strange then, that it is in this period that Markino would have a brief encounter with the murky world of espionage and secret diplomacy with which Hisaakira Kano just a few years later would become intimately acquainted. As the quote that opens this section states, Markino’s 1929 Knightsbridge exhibition was opened by ‘Colonel, the Master of Sempill’. This was William Francis Forbes-Sempill, the future 19th Lord Sempill, a Scottish aristocrat, aviator, Japanophile, and spy—witting or otherwise—for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) [18].

The future Lord Sempill showing a Japanese naval officer around an aeroplane, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=427653

In 1921, ‘Wully’ Sempill, as he was known to his friends, led a British Aviation Mission to Japan to train IJN aviators. On his return to the UK, he felt the need to defend this activity in the press, explaining in a letter to the Civil and Military Gazette (Lahore) his view that if Britain did not supply such help to Japan, its enemies would, with a concomitant loss of British influence with Asia’s pre-eminent power. Sempill became a consultant to aviation companies, and the need to drum up trade, along with his view that keeping Japan ‘on-side’ was in Britain’s interests, led him to be what can most charitably be described as ‘indiscrete’ in the information that he supplied to the Japanese naval attaché in London in an attempt to curry favour. This brought Sempill to the attention of MI5, and, on their advice, in 1926, Sempill was informed that he would no longer be allowed access to information that may be of use to a foreign power. Sempill fumed, but ultimately, on the advice of friends, accepted the rebuff. He spent the next decade out of favour with the government. However, that changed with the outbreak of the European war in September 1939. Sempill was given a job in the Admiralty connected to naval aviation. For his Japanese friends, this would prove too good an opportunity to pass up.

By 1939, prime amongst those friends was Hisaakira Kano.

Hisaakira Kano returned to London with his wife Tatsu and youngest daughter Rosa Hideko (then 13) in 1934 (the Kanos’ other children were by then either married or studying in Japan) [19]. Kano had returned to take charge of the London branch of the YSB. He arrived to find Anglo-Japanese at a historic low ebb. Ironically, for the anglophile Kano, this was in part his fault, as, when he left London in 1924, it was to take charge of the YSB’s Calcutta (modern Kolkata) branch. His main achievement during that posting was creating the financial instruments that smoothed the way for Japanese textile firms to trade with India in direct competition with British firms. This was the origin of a trade war that would spring fully into life in the next decade.

However, more than worsening trade relations, it was Britain’s opposition to Japanese actions in China that had brought Anglo-Japanese relations to an impasse. The previous year, Japan had withdrawn from the League of Nations in protest at Western criticism of its actions in Manchuria and Northern China. A military confrontation between the Western powers and the Empire of Japan was now a real possibility—there had already been incidents at flashpoints like the international settlements in Tientsin (modern Tianjin) and Shanghai. To the pacifist Kano, this was a situation he could not ignore. Although he had maintained a quiet home life in the suburbs during his previous London posting, on his return in 1934, he decided to rent a townhouse in the city centre. There, he and Tatsu set about hosting twice-weekly dinner parties to which they invited the great and the good of the British establishment, alongside members of the Japanese community in London that Kano knew to share his views, philosophy, and faith. Kano was intent, for the sake of peace, on being a bridge between the governments of the UK and Japan.

However, in the midst of this, Kano experienced personal tragedy when, in May 1935, his wife, Tatsu Ito Kano, died as a result of an undiagnosed heart condition, aged just 43. Kano was in Switzerland at the time attending a meeting of the International Bank of Settlements, and could not immediately return to London. So, it was left to his 14-year-old daughter Rosa Hideko Kano to handle arrangements until his return. Tatsu Ito Kano was cremated, some of her ashes being returned to Japan and the rest being buried in a grave in Hendon Cemetery. At the graveside, Kano sang a Schumann lieder that the composer had dedicated to his own wife, Clara (Widmung from Myrthen, Op. 25). When, after a period of mourning, he renewed his charm offensive against the British establishment, he would rely on the 14-year-old Rosa to play the role of hostess. This embrace of British upper-class society would culminate, in the Spring of 1939, with a now 18-year-old Rosa making her debut at court (becoming what was known as a debutante or ‘deb’), an event that received considerable press attention at the time [20].

Wully Sempill, the newly minted 19th Lord Sempill, was a frequent visitor at the Kano soirees. As was, from 1936 onwards, the new Japanese ambassador to the Court of St James, Shigeru Yoshida (吉田 茂, Yoshida Shigeru). Yoshida, who would go on to be a post-war prime minister of Japan, believed as strongly as Kano did that the future prosperity of Japan lay in maintaining friendly relations with the Western powers. He stood in opposition to both the military domination of civilian government in Japan and Japan’s burgeoning friendship with Hitler’s Germany. Together, he and Kano would form what some modern scholars have characterised as a ‘conspiracy’ to thwart the ambitions of the pro-military pro-Nazi elements of the Japanese government by maintaining a secret line of communication to the British government via key contacts like Sempill. They were guided in their approach by information supplied to them by contacts in the cabinet of Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe (近衞 文麿, Konoe Fumimaro), chief among them, Minister of Education Koichi Kido (木戸幸一, Kido Koichi) [21].

When Yasuhito, Prince Chichibu (秩父宮雍仁親王, Chichibu-no-miya Yasuhito Shinnō), brother of the Shōwa Emperor, arrived in the UK in the Spring of 1937 to represent the Emperor at the Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, he and his wife were met at Southampton by Yoshida. They all then travelled to London by train. Waiting to greet them at Waterloo was a crowd of thousands and an old friend of the Prince: Lord Sempill. The prince and princess’s schedule while they were in the UK was handled by Hisaakira Kano. This renewing of his friendship with the Japanese royal family, orchestrated by Yoshida and Kano, strengthened the depth of Sempill’s connection to the interests of Japan. Yoshida would be recalled by Tokyo in 1938 in large part because of his active commitment to engaging with the British government over China, which ran counter to the strengthing belief among the military faction in Japan that the Empire’s future lay in an alliance with Hitler’s Germany. Yoshida would be replaced as Japanese Ambassador to the Court of St James by Mamoru Shigemitsu.

The Very Thing I Live For

“I always compare the genuine friendship with the water. Sometimes we forget the benefits which the water gives to us. Sometimes we are very ungrateful to it. But how earnestly we long for it when we are away from it for only a few hours! So with friends! Indeed friendship is the very thing I live for.”

As far as we can tell, Markino and Shigemitsu had not seen each other for over 20 years when Shigemitsu arrived back in London in the autumn of 1938 and yet, they returned at once to the close friendship that they had once known, which would last for the rest of Markino’s life. Shigemitsu also renewed his acquaintance with Kano, which began in their university days. In Shigemitsu, Kano found another fellow traveller, a man committed to rebuilding relations with the Western powers and trying to steer Japan away from an alliance with Hitler’s Germany. While in Markino, Shigemitsu found a friend who offered him a respite from the growing pressures of what was rapidly becoming an impossible task: serving his country loyally while believing that it was heading toward disaster.

In London, through the week, Shigemitsu would work via Kano and his contacts in the British establishment—Sempill prime amongst them—to try to move the British government away from positions that the military faction in Tokyo would see as a red line. In the country, at the weekend, Markino would entertain Shigemitsu with idiosyncratic tales of the life he had led while the two friends had been apart. Markino, who would not have ever sought to involve himself in politics or diplomacy was now, in his own small way, helping Shigemitsu recharge his mental batteries [23].

Yoshio Markino, jacket design, Recollections and Reflections, 1913. Public domain.

The outbreak of the European war in September 1939 came as a profound shock to the London Japanese, even with all the warning signs. It was at this moment that Shigemitsu offered Markino (and his cat) refuge in the embassy—which would also allow him to meet with his old friend whenever he had free time, even if only for a few minutes of conversation over coffee or a hurried meal of sukiyaki. Meanwhile, he issued advice to Japanese companies—like the YSB—with Japanese staff in the UK to send any who could be spared back home, along with all Japanese family members, even those of staff who had to stay. For now, this advice was primarily aimed at short-term residents. These were primarily employees seconded to the London branches of the companies for which they worked; men (and it was mostly men) without strong links to the UK, some of whom had brought their families with them from Japan. Longer-term residents—including men who had married British women and fathered children in the UK—whose entire livelihoods were the businesses or careers they had created in the UK were not yet expected to make the very difficult decision to leave.

This can be seen by reviewing the passenger list of the Hakone Maru, the NYK line ship that left Liverpool on 10 October 1939 with the first group of returnees. Of the nearly 199 Japanese nationals onboard, 150 were UK residents; of these, 64 were women travelling without partners (there were only nine couples onboard), and 54 were children. Only one of the passengers had a Western given name, 14-year-old Jean Tsunoda, and she was the daughter of Saburo and Yuki Tsunoda née Okamoto (Saburo Tsunoda—a rare longterm resident among the passengers (he had arrived in the UK in 1913)¬—was travelling with his daughter; I have been unable to determine where his wife Yuki and their other surviving child, June Tsunoda, were). Those female returnees with professions listed included nurses, cooks, maidservants, and students; the few men onboard not in transit, included lampshade makers, a lacquer worker (Saburo Tsunoda), clerks, and a chick sexer [24].

The women and children returning to Japan onboard the Hakone Maru included dependents of YSB staff, Rosa Hideko Kano among them. Kano was sending his daughter out of harm’s way, but he was also returning her to Japan to marry the husband that he had picked out for her, a family acquaintance, the tennis player and later businessman Eikichi Itoh (伊藤英吉, Ito Eikichi), heir to what is now the Itochu Corporation. The couple would go on to become stalwarts of Anglo-Japanese friendship. Author and historian Keiko Itoh is their daughter.

The overwhelming impression is one of a community recognising the seriousness of the situation but not yet alarmed, of families of Japanese employees seconded to London who would have returned to Japan at some point anyway, simply returning earlier than planned.

This should be contrasted with the last ship to leave the British Isles with returnees, the Husini Maru, which left Galway in Ireland bound for New York on 6 November 1940. Here, there were more men than women and children among the returnees. Their professions ranged from hotel-keeper to music hall artist; there were professors of philosophy, shipping agents, merchants, art dealers, restaurant owners, company employees, bank clerks (from the YSB and the Bank of Taiwan), hairdressers, and poultry breeders. And there were the partners and dependents of these men, British, French, and in one case, German women—Anna Amelia Kato, Angela Kawabata, Annie Elizabeth Nakano, Janet Iwano, Margaret Miyaguchi, Kate Cleavely Oshima, Dorothy Sato, Genevieve Tamaki, Eileen Minnie Takasaki, Winifred Yamaguchi, and Violet Edna Yoshima—and their children, the youngest, just one-year-old (Thomas Hideo Nogi) [25]. This was a community in full flight, men and women making the most difficult of decisions, to abandon the lives that they had made for themselves in the country they called home; they were in a very real sense, refugees. When they left, the London Blitz was at its height; the city had experienced nearly two months of nightly bombing. The refugees’ only solace was that they were leaving a country that was under enemy attack for one that was not. Yet.

Due to the suddenness of the outbreak of the European war, there were passengers already at sea when war was declared. These included those passengers who arrived in the UK onboard the Hakone Maru, the ship that would carry the first of the Japanese London returnees home. One such passenger was future Nile voyager, 29-year-old Sachiko Murauchi (村田幸子, Murauchi Sachiko), who had arrived to take up a post as a private secretary at the Japanese Embassy in London. Just over a year later, Sachiko Murauchi would become the Second Lady Kano [26]. Another arrivée in this period was pianist Chieko Hara (原智恵子, Hara Chieko; later Chieko Hara-Cassadó), although in her case from her home in Paris. She had travelled to the UK to play a series of concerts only to find on her arrival that all public performances were cancelled. After giving two private recitals—including one at the Japanese Embassy—she left for concerts in the USA in November 1939 [27]. It would be of pleasing economy if Chieko Hara’s recital at the Japanese Embassy was where Hisaakira Kano and Sachiko Murauchi met. And if Embassy resident Yoshio Markino were in the audience too.

Pulled out at the Root

“…to the surprise of everybody the flowers never wither, because the herald had pulled out the roots together”

As the Blitz raged over London, Kano and Shigemitsu, working often through Sempill, continued to try to move the British government in a direction that would check the military faction in Tokyo’s attempts to create a pact with Hitler and Mussolini. When the pact was eventually signed in September 1940, the writing was on the wall for Shigemitsu’s time as ambassador; he had made too many enemies among the triumphant pro-Axis camp. However, in the meantime, he continued working to bring the British and Japanese to some kind of concord, which came to focus on persuading the government to send an envoy to Japan for direct talks. By this time, Kano and Shigemitsu’s use of Sempill, as well as Sempill’s own independent lobbying, had brought him back to the attention of MI5, something that was so widely known in Whitehall that government officials were writing about it in their diaries, with Permanent Under-Secretary Sir Alexander Cadogan describing Sempill has having been ‘..completely hoodwinked by the [Japanese]’ in one entry [29]. This was in the summer of 1941 and coincided with Shigemitsu’s long-foretold recall to Tokyo. Sempill’s final fall from grace would happen in November 1941 under what are today disputed circumstances. What is not in dispute, is that he was dismissed from his admiralty post at Churchill’s instruction. Less certain are the events leading up to it. In recent times, it has been suggested that Sempill leaked to his Japanese ‘paymasters’ details on the Atlantic Charter—the alliance between the USA and the British Empire—and finding out about the Charter prompted the Japanese government to decide that war with the Western powers was inevitable and better to strike first. However, some scholars have poured cold water on this idea [30].

Before Shigemitsu left London, as recounted above, he left his great friend Markino a line of credit at the YSB. It is impossible to believe that he did not first ask his friend to return with him to Japan. So we can only suppose that Markino refused to leave his beloved London, despite all the signs pointing only one way, toward conflict between his birth and adopted countries.

When the blow finally fell, and the news was announced that the Empire of Japan had attacked Western possessions in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, Kano made a tearful speech to the assembled employees of the London Branch of the YSB¬—British and Japanese lamenting the turn of events. Most of the Japanese staff would be arrested and interned the same day (the 8th, the day after the attacks), and the bank would be seized by British authorities. Two employees were not immediately interned, however: Kano himself and Katsura Takashima, the husband of Hilda May Takashima née Locke. In the case of the latter, this can only have been because of his English wife.

Someone else who escaped immediate internment was Markino. As I have discussed elsewhere, this was also true of other long-term Japanese residents, such as silk merchant Koichi Kaji and former shop owner and current civilian employee of the Japanese military attaché, Koichi Nishikawa [31]. However, unlike the others named, Markino would remain free until he and the other residents of the embassy were repatriated. When the Luftwaffe’s bombs began to fall on London, he climbed up onto the Embassy roof to watch, entranced by the colours. He remained the observer, the artist, the detached [32].

"Pall Mall (22058955226)" by Leonard Bentley from Iden, East Sussex, UK is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Kano would likely also have remained free until repatriated had it not been for his insistence on continuing to try to smooth over Japanese and British relations even in the middle of a war. When asked by the press in March 1942 about alleged Japanese atrocities during the invasion of Hong Kong, Kano felt compelled to call such stories Chinese propaganda. This was too much for the Home Office, and within days, Kano found himself arrested and transferred to an internment camp on the Isle of Man. Sachiko, Lady Kano, would visit him there in May. Two of the island’s hotels refused to rent her a room and she had to spend the night in a boarding house [33].

It was around this time that plans for the first round of exchanges of British and Japanese civilians were finalised [34]. The exchanges were to take place in the neutral port of Lourenço Marques, Portuguese East Africa (now Maputo in Mozambique). The first of a planned series of exchanges involved over 1800 men, women, and children, British and Commonwealth on one side, Japanese and Thai on the other (Thailand had become an ally of Japan in December 1941 and declared war on Britain and the US in January 1942). Only a handful of the Japanese and Thai contingent would be travelling from the UK, around 80 Japanese nationals and 40 Thai nationals (in the event, it would be 76 Japanese Nationals and around 40 Thai nationals; the list of Japanese repatriates along with the sources can be found here). Their journey to East Africa would be onboard El Nil.

Hisaakira Kano and the rest of the interned YSB staff—including Takashima (interned in late June 1942 in anticipation of repatriation)—would be included in the first exchange, as would be the staff of the Japanese Embassy, including Yoshio Markino. Travelling to Japan with their husbands would be Sachiko, Lady Kano, and Hilda May Takashima. Lady Kano travelled up from London to Liverpool, the port of departure, with the staff from the Embassy and Markino on Saturday 18 July 1942 [35]. I have been unable to determine when Hilda May Takashima made the same journey.

El Nil. Ashashyou, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

It is worth noting here that El Nil would be carrying at least two more female repatriates, both Thai nationals: Lamon Sombuntham, a student studying medicine in Dublin, and Jean Hu Wasson, who had been born in China, the daughter of English missionaries, and had become a Thai national when she married her Thai fiancé, Dublin doctor Sebastian Lert Srichandra, days before El Nil’s scheduled departure. As with the Dublin contingent, the majority of the Thai nationals repatriated from England were students, alongside the Thai minister in London, Phra Manuvedya Vimolnard, and two other legation officials [36].

After two false starts, El Nil finally left for East Africa on 29 July 1942. This was to prove the only exchange, as a second exchange was aborted at the last minute because of arguments over the status of Japanese merchant mariners in Allied hands—the cancellation was so last minute that a small batch of Japanese repatriates had already sailed from England. Instead of going home, they would spend the rest of the war interned in India [37].

The Japanese repatriates arrived back in Japan in late 1942. What happened to them afterward lies outside the scope of this article, but it is worth noting that Kano, Shigemitsu, and Markino all survived the war. Shigemitsu was one of the two Japanese signatories of the official surrender signed onboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945. Postwar, both Kano and Shigemitsu would be censured by the victorious allies, with Shigemitsu serving several years in prison, but both men would go on to play active roles in rehabilitating Japan’s reputation with the international community. Markino became a permanent guest of the Shigemitsu family. Despite living for another ten years after the end of the war, he never returned to London. However, this should not be seen as a surprise, as the London he had known had vanished forever with the dissolution of the London Japanese community. As Markino’s great friend Yone Noguchi had once written, it had danced ‘wild as a fire only to vanish away’ [38].

Jamie Barras, February 2025

Notes

Yoshio Markino, A Japanese Artist in London (London: Chatto & Windus, 1911), 96.

According to a Belasco biographer, the Darling of the Gods had its origins in an unproduced play written by Belasco with an Italian setting; Long was then brought on board to turn it into a Japanese-themed story: William Winter, The Life and David Belasco, Volume 2, (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1918), 67. ‘Gorgeous Claptrap’: Tatler, 28 January 1914. The roles of Genjiro Yeto and Yoshio Markino in the New York and London productions of Darling of the Gods: Lydia Edwards. "A Tale of Three Designers: The Mystery of Design Attribution in Belaso and Long’s The Darling of the Gods Staged at His Majesty’s Theatre, London, in 1903." Theatre Notebook 69, no. 2 (2015): 97-112. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/636742. A script for the play complete with stage manager notes is available to download at archive.org: https://archive.org/details/darlingofgods00bela, accessed 8 February 2025. Although all the actors were white in the 1903 New York and 1904 London productions, the 1914 London revival featured a genuine Japanese actress in a minor role; I tell her story here: https://www.ishilearn.com/wata-san.

Yone Noguchi, ‘Yoshio Markino’, Japan Times, 4 March 1917.

My main source for the broadstrokes of Yoshio Markino’s life in London is Keiko Itoh, The Japanese Community in Pre-War Britain, (London: Routledge, 2001), 111–113 and 118–119. The details are drawn from Yoshio Markino, 1869—1956 in Hugh Cortazzi with James McMullen and Mary-Grace Browning (eds), Carmen Blacker: Scholar of Japanese Religion, Myth and Folklore: Writings and Reflections (Amsterdam University Press, 2017), 234–48, and Markino’s own writings, principally A Japanese Artist in London (See Note 1, above). The story of his renewed friendship with Yone Noguchi on Noguchi’s first visit to London is told in A Japanese Artist in London on pages 64–67. That story and the story of their reacquaintance a second time on Noguchi’s second visit to London is told from Noguchi’s perspective in the article in Note 3 above. Markino is listed as an ‘author & artist (resident guest at Embassy)’ in the 1939 England and Wales Register, accessed at ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com, Inc., 24 January 2025.

The story of the £300 is told by Keiko Itoh quoting an account by Betty Shephard (Note 4 above, first reference, 119).

Yoshio Markino, When I was a Child (London: Constable & Company Limited, 1912), 6.

History of the YSB taken from here: Makoto Kasuya, 2009. "The Activities of a Japanese Bank in the Interwar Financial Centers: A Case of the Yokohama Specie Bank," CARF F-Series CARF-F-146, Center for Advanced Research in Finance, Faculty of Economics, The University of Tokyo. I tell the story of the decline of the Japanese textile trade here: https://www.ishilearn.com/nile-voyagers-silk, accessed 9 February 2025.

The details of Hisaakira Kano’s life I have largely taken from a biography in Japanese, 高崎 哲郎, 国際人・加納久朗の生涯, 鹿島出版会, 2014 (Tetsuro Takasaki, The Life of Hisaakira Kano, Internationalist (Tokyo: Kajima Press, 2014), downloaded, chapter by chapter, from https://www.ur-net.go.jp/, accessed 11 February 2025. This is supplemented by passages in Keiko Itoh (Note 4 above, first reference).

Rosa Hideko Kano is the mother of Keiko Itoh, see Note 4, above, first reference.

The Takashimas’ story can be pieced together from public records. These include the following: the marriage registration for Hilda May Locke and Katsura Takashima, accessed at https://www.freebmd.org.uk/, 12 February 2025. England, birth certificate (certified copy) for Vera Phillip(s) Locke; registered 22 October 1917, Willesden; General Registry Office. England, marriage certificate (certified copy) for Walter Sydney Davies and Vera Philip Locke, otherwise Eileen Vera Hartin; registered 31 May 1936, Coventry; General Registry Office. 1921 England Census entries for Hilda May Locke and Katsura Takashima; Hilda May Takashima’s return to the UK, with marital status given as ‘widow’, passenger list for SS Empress of Scotland, arrived Liverpool, 26 July 1947, UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960, accessed at ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com, Inc, 12 February 2025.

Note 1 above, 127.

This is the version of the story told by Keiko Itoh, drawing on Markino’s own writing, see Note 4 above, first reference, 112.

This story can be pieced together from documents and period newspaper accounts, principally: Marriage Register for ‘Earle Uffington’ and ‘Marie Eugenie Pardoe’ (amended), London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1938; entry for Earle Uffington, UK, After-Trial Calendar of Prisoners, 1855-1931; naturalization declaration of Marie Eugenie Piron, 1943, Massachusetts, U.S., State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1798-1950; all accessed at ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com, Inc., on 11 February 2025. ‘Alleged Bogus Son of an Earl’, London Daily Chronicle, 4 April 1919, and ‘Man Who Said He Was Lord Craven’, Nottingham Journal, 23 May 1919.

Viscount Uffington bankrupt and the identity of his mother: ‘High-Born Debtors’, Aberdeen Daily Journal, 19 September 1919. Death of the 4th Earl: ‘Earl of Craven Drowned’, Daily Telegraph (Derby), 11 July 1921. Viscount Uffington, afterwards the 5th Earl, would himself die of peritonitis in 1932, aged just 35: ‘Earl of Craven Dead’, Dundee Courier, 17 September 1932.

‘Hyde Park By Night: Japanese Painter’s Exhibition.’ Scotsman, 4 April 1929.

See Note 15 above.

Review: ‘Art in London’, Scotsman, 2 February 1933; ‘living in seclusion’: Pall Mall Writes, Gloucester Citizen, 22 October 1933; Quote from Who’s Who: ‘Recreations of the Famous’, Evening Telegraph (Derby), 18 December 1934.

My information about Sempill’s activities comes from: Alex Hardie, Sempill, Japan, and Pearl Harbor: Traitor or Spy-Myth?, International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 2023, 36:3, 932-967, DOI:10.1080/08850607.2022.2081048.

Once again, my main source on the details of this stage in Kano’s life is the Takasaki biography, in this case, chapters 8 and 9; see Note 8 above.

Rosa Hideko Kano as debutante: the Sketch was just one of the many British publications that featured Rosa Kano prominently in its coverage of the 1939 debutante season. See photo story in the Sketch, 15 March 1939.

This aspect of the Kano story, his biographer Takasaki turned into an article that can be read [in Japanese] here: https://www.risktaisaku.com/articles/-/6762, accessed 13 February 2025.

Yoshio Markino, My Recollections and Reflections (London: Chatto & Windus, 1913), 2.

This aspect of the Shigemitsu–Markino relationship I take from the account given by Keiko Itoh (Note 4 above, first reference, 119) of the memoirs of Betty Shephard, a friend to both Markino and Shigemitsu.

Passenger list for the Hakone Maru, departing Liverpool 10 October 1939, UK and Ireland, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960, at ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry Operations Inc., accessed 10 February 2025. The name of Jean Tsunoda’s mother can be seen from the record of her birth in early 1925 and her parent’s marriage in early 1924, accessed at https://www.freebmd.org.uk/, 13 February 2025. For the story of the Japanese lampshade makers in London, see Keiko Itoh (Note 4 above, first reference, 72), for the story of Japanese chick sexers in England see Keiko Itoh (Note 4 above, first reference, 61–66) and https://www.ishilearn.com/nile-voyagers-lightning-hands, accessed 13 February 2025.

Keiko Itoh identifies this ship the Fushimi Maru (Note 4 above, first reference, 183) but the landing records at New York give the name as Husini Maru, a different ship operated by the same line. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, accessed at ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com, Inc., 10 February 2025.

Takasaki biography, Chapter 10; See Note 8 above.

‘Japan’s No 1 Pianist Leaves England Unheard’, Lincolnshire Echo, 16 November 1939. The other recital was ‘at the Japanese Club before Viscount Kano’. The information that Hara was living in Paris in1939 comes from: Rie Ando, Chieko Hara—a life and art, University of Washington ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2010. 3421551.

See Note 27 above, 195.

This diary entry is quoted in Hardie (Note 18 above, 945).

Hardie prime among them, Note 18 above.

The timing of the internment of YSB staff can be reconstructed from UK internment records: UK, World War II Alien Internees, 1939-1945’, accessed at ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., on 11 November 2024. I tell the stories of Koichi Nishikawa and Koichi Kaji here: https://www.ishilearn.com/nile-voyagers-silk, accessed 14 February 2025.

The story is told by Carmen Blacker, Note 4 above, second reference.

‘Viscount Kano Interned’, Daily Herald, 12 March 1942. ‘Hotels Bans Jap Viscountess’, Daily Mirror, 14 May 1942.

For the background to the exchange, see: Rowena Ward, Repatriating the Japanese from New Caledonia, 1941-46. The Journal of Pacific History, 2016, 51(4), 392–408. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26157713.

‘Jap Diplomats Go in Secret’, Sunday Express, 19 July 1942.

Sombantham and Wasson are named in: ‘Anglo-Japanese Exchange of Nationals’, Irish Independent, 20 July 1942. Wasson and Srichandra’s story is told in: Rev. Patrick O’Connor S.S.C., ‘Thailand Shamrock: Doctor, Once Buddhist Monk, Spiritual Son of St. Patrick’, Catholic Advocate, 14 March 1963. Information on the other Thai repatriates: https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/the-free-thai-movement-and-the-soe/, accessed 9 March 2025.

Rowena Ward, The Asia-Pacific War and the Failed Second Anglo-Japanese Civilian Exchange, 1942-45, The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2015, 13, Article ID 4301; https://apjjf.org/2015/13/11/rowena-ward/4301, accessed 15 February 2025.

Yone Noguchi, Ghosts of Abyss, first published in The Pilgrimage, 1909.