Rivers and the Black Swan

Jamie Barras

“The BLACK SWAN TRIO, and the Royal BROTHERS BOHEE (JAMES D. and GEORGE B.). Orchestral and Military Bands. A superb Combination of genuine and original Coloured Talent.”

When, in the autumn of 1888, the Bohee brothers, Black Canadian banjo players to royalty [2], created their first English touring minstrel troupe, they populated it with other African American and Black Canadian performers, setting themselves apart from the mainly ‘blackface’ minstrel troupes abroad in England at the time. The troupe would for the next ten years feature a host of African American and Black Canadian performers, providing work and stage experience to artists who would otherwise struggle to find both, but at the same time helping to perpetuate the negative stereotypes of African Americans that were the stock-in-trade of blackface minstrel troupes, leading to a contested legacy [3].

The Black Swan Trio: (left to right) Isaac Jones, Corlene Cushman, and Josie Rivers. Music Hall and Theatre Review, 25 November 1892. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

In the Bohee troupe’s first incarnation, its undoubted stars—in addition to the brothers themselves—were two female performers, members of a combination known as the “Black Swan Trio” [4]: Corlene Cushman, a soprano whose billing of the “Black Swan” gave the trio its name, and a child performer called “Little” Josie Rivers (the third member of the trio was a performer named Isaac Jones, whom we will meet later). In this article, I use the lives and careers of Corlene Cushman and Josie Rivers to examine the challenges that female performing artists of colour faced in this period, some of which mirrored those of their male counterparts, some of which were unique to their situation, and how these challenges shaped their staged identities.

Some of the earliest African American performers to make an impact in the UK were women. Prima donna Elizabeth Greenfield, the original “Black Swan”, toured England in 1853, albeit to a mixed reception, cemented by critics who viewed her through the lens of minstrelsy [5]; and she was just one of a number of African American prima donnas who found fame in the second half of the nineteenth century [6]. Corlene Cushman modelled her career—or at least attempted to, as we will see—on the likes of Greenfield, Madame Selika, and Sissieretta Jones (Josie Rivers became a performer at far too young an age to have received any formal training). This is most obvious in Cushman’s adoption of Greenfield’s “Black Swan” billing but also in her aspiration to perform in concert halls.

Elizabeth Greenfield, the Original Black Swan. New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1005e100-c5f5-012f-d504-58d385a7bc34 . Public Domain.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers. New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/171daed0-c606-012f-07b3-58d385a7bc34. Public Domain

Sissieretta Jones, the “Black Patti”. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian. https://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=record_ID=npg_NPG.2009.37 Public Domain.

To this list of pioneering solo singers can be added those women of colour who found fame performing in vocal groups, most notably the female members of the Fisk Jubilee Singers [7]. The Jubilee Singers were a co-ed a cappella group formed of students of Fisk University and sent on tour by the university to raise funds for the struggling institution (although, by the late 1870s, the group was operating independently of the university—and, indeed, had split into at least two groups). In their various incarnations, the Fisk Jubilee Singers toured Europe several times in the 1870s and 1880s. Most of the original members of the group were born into slavery—a fact that featured prominently in their billing—and their original repertoire was centred on what was known variably as “slave songs” or “negro spirituals”. It is, therefore, somewhat depressing to report that the importance to Fisk’s finances of the group’s tours meant that all but one of its original members were kept on the road for so long that they failed to graduate, robbing them of their goal in attending Fisk in the first place, the gaining of a college degree [8].

The form of entertainment offered by the Fisk Jubilee Singers was distinct from minstrelsy in its conception—and in its realisation by the genuine Fisk singers—however, the lines rapidly became blurred once imitators began to appear, particularly in England; and it is notable that all three strands of performance—solo and choral singing and minstrelsy—are irretrievably entwined in the case of the careers of Corlene Cushman and Josie Rivers.

“TROY GOSSIP. Miss Caroline Cushman, sister of Mrs W B Keyes, arrived here last Wednesday from Milwaukee, where she closed a successful engagement in one of the leading opera houses. She left on Friday last to fill an engagement in Providence. Miss Cushman is better known as the “Black Swan”. ”

The first mention of the prima donna billed variably as Corlene, Coraline, Carline, or Caroline Cushman (1852–1894) in the press appears in the winter of 1883. This is in a review of a performance of “Her Majesty’s Colored Minstrels” at the Academy of Music in Montreal, Quebec. Interestingly, Cushman at this nascent stage of her career is billed as the “Black Swan Jr”, acknowledging Greenfield as the original. Not for the last time, Cushman was one of the few performers on stage that evening to receive a positive notice [10].

As we have already seen, Cushman took her billing from Elizabeth Greenfield, and it seems just as clear that she took her stage name from the [white] actress and prima donna Charlotte Cushman. However, it is also probably significant that one of the most prominent blackface minstrels of this period was Frank Cushman, who made frequent appearances in Montreal, including just a few months before Corlene Cushman’s debut [11]. As to her real name? The “Mrs W B Keyes”, sister of Caroline Cushman, of the above quote can be identified as Mirian Jackson, wife of William B Keyes of Troy, New York, and we know from reports in the UK stage press that Corlene Cushman’s mother’s name was Phebe Jackson and the family came originally from Utica, New York. The final piece of information we have is that Corlene Cushman was born around 1852 [12].

From the above three pieces of information, we can trace back the family history using US Federal and New York State censuses (which include information on race). In 1875, William B Keyes was a lodger in a boarding house kept by Mrs Phoebe Jackson in Utica, New York. Mrs Jackson’s daughter Marrian was also living there, as was an older woman named Sarah Jackson (and others). From here, we can trace the family back via the 1870 Federal Census to the New York State Censuses of 1865 and 1860, where we find Mrs Phoebe Jackson, her daughter Marion, and an older woman named Sarah Jackson living with a number of Mrs Jackson’s other children and several boarders. Those children include three more girls, Nancy, born 1850, Sarah, born 1851, and Nettie, born 1857 [13]. It is highly likely that Corlene Cushman was one of the two older girls, although uncertainties over recorded ages in this period make it difficult to determine which. We know that later in her life she also went by the name Nellie [14], which may suggest that she was Nancy Jackson (or even Nettie Jackson, given the uncertainties in ages). However, this cannot be determined with any certainty, as official records are hard to come by, a situation that is complicated, as always with performing artists, by Cushman/Jackson’s use of a stage name.

It is also worth noting here that Cushman was already 30 years old by the time she appeared on the Montreal stage, which leaves a large part of her life—the years between 1865 and 1883—as yet unexplored. We know she was not living at home in 1870 but where was she? It may be significant in this context that the original Black Swan, Elizabeth Greenfield, was a music teacher in Philadelphia in this period, and formed an opera troupe with some of her students and former students [15]—was Jackson/Cushman a student of Greenfield, is that the origin of her original billing “Black Swan Jr”? Research is ongoing.

As we can see from the quote above, irrespective of its origin, by the summer of 1884, Cushman’s “Black Swan Jr” billing had been shortened to “Black Swan”. Remarkably, for a brief time in the Spring of 1884, she was even billed as “The Great Patti of the Colored Race”, a nod to superstar Italian prima donna Adelina Patti, a billing that predates the earliest use of “the Black Patti” to describe Sissieretta Jones by a good four years [16]. However, despite the picture this might paint, and although we can point to an appearance at the “Grand opera house” in Saint Paul, Minnesota (as part of a “minstrel festival”) and a claim that Cushman had been educated in Europe in the true prima donna style [17], the reality was that she performed mostly in dime museums.

“Broadway & Trevser’s Dime Museum presents an excellent array of features for next week […] Chemah, the celebrated Chinese dwarf […] two performing donkeys […] the Albino Queen, and Carline Cushman, the “Black Swan”. ”

Source: Digital Museum of America. No known copyright owner.

Dime Museums were indoor circus sideshows complete with cabinets of curiosities, exhibitions of biological rarities (“freak shows”), electrical gadgets, and variety-style entertainment. They owed their origin and took their name from P T Barnum’s “American Museum” in New York, which charged a dime for admission [19]. In terms of music venues, they were equivalent to the original music halls of England, adjuncts to public houses, albeit aimed more at women and children on a day out than male drinkers on a night out (although they did feature burlesque dancers). They were the definition of “lowbrow”. For someone who aspired to appear in opera houses—for someone who claimed to be doing just that—they were a stage of almost last resort and represented the distance between the aspirations of a young vocalist, inspired by the female singers of colour who had gone before her, and the reality of the opportunities open to the vast majority of African American performers, whatever their talents.

Cushman appeared at dime museums across the American northeast and as far west as Missouri from the spring of 1884 until the autumn of 1887. It was during an appearance at the Austin & Stone Museum and Theatre in Boston in June of 1886 that we first see her path cross with one of her future partners in the Black Swan Trio: the “petite child artiste” Josie Rivers [20].

“Corlene Cushman, who is well known in this city under the sobriquet of the “black swan,” is a very pleasing little artiste, as is also Josie Rivers, a pretty Creole child, whose vocal accomplishments are of no mean order. ”

Josie Rivers (1877–1963) was born Josephine Rivers in Columbus, Missouri, in 1877, making her nine or ten when Cushman first encountered her. Her mother’s name was Mary, and she had an older sister called Lena. I have to date been unable to determine the name of her father. In around 1883, Mary Rivers married a man named William Jacobs and moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where she would remain for at least the next 17 years [22].

Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine from newspaper reports how much of a role in Josie’s career either her mother or stepfather had; however, subsequent events would suggest that Josie was travelling with other performers rather than her parents and/or sister. Child performers were, of course, not unusual in the late nineteenth century—it was the so-called “golden age” of the child performer; a record number of children appeared on stage in this period. When the UK government proposed a bill in 1889 to ban children younger than 10 from performing on stage, the poet Ernest “Days of Wine and Roses” Dowson published an essay in defence of the practice titled “The Cult of the Child”; in it, he wrote, “to let children go on the stage is, after all, to do nothing worse than to cultivate their playful instinct” [23]. Although Dowson was a man who spent far too much time thinking about the admirable qualities of children, his defence of child performers is illustrative of what was at the time a mainstream view. Nor were children living separately from their parents rare in this period, regardless of social class—be it for work or schooling. Josie Rivers’ situation must be viewed in this light.

According to one report, Rivers started her performing career as a member of a group of child entertainers [24]; however, while this may be true, I have been able only to trace her as a solo performer. By age 10, she was already a solo singer, dancer, and male impersonator. Like Cushman, and as can be seen from the quote above, she was often singled out for praise in reviews of bills on which she appeared and indeed, often described as the top draw, a testament both to the appeal of child performers to Victorian audiences and Josie Rivers’ talents.

Cushman and Rivers continued to appear on the same bill at various dime museums across the next year, and there is evidence that this was because they had become part of the same minstrel troupe (the ‘Harry Morris combination’ [25]). Significantly, as early as February of 1887, they were also sharing the bill with the final future member of the Black Swan Trio, Isaac ‘Ike’ Jones [26].

Isaac Jones (1860-?) is something of an enigma. This was likely his real name—it is certainly the name he used on the few official records that we have for him. He was born in Toronto, Ontario, in or around 1860 [27]. Described as a “colored baritone”, he was a member of a troupe of black performing artists, the Kersands Minstrels, in the years immediately preceding 1887 [28]. This is in itself worthy of note, as before creating his own troupe, Billy Kersands was a member of Haverly’s United Mastodon Minstrels Troupe alongside the Bohee brothers and had gone with the troupe to England in 1881, an engagement that had ended in the Bohees deciding to settle in the country [29]. Was this the entrée for the Black Swan Trio into the Bohee Brothers troupe in England? Regardless, this is the only information that, to date, we have for Ike Jones before his time in England. As to how much contact, if any, he had had with either Cushman or Rivers before appearing on the bill with them in February 1887? Although I have been unable to find a definitive answer to that question, it is worth noting that Corlene Cushman appeared on the same bill as Billy Kersands in June 1884 [30]. This appears to be before Kersands formed his troupe, however, and there is nothing to suggest that Jones was working with him at this time. Certainly, Kersands and Cushman, and by extension, Cushman and Jones, followed separate career paths between that date and February 1887.

Haverly’s United Mastodon Minstrels. Digital Library of America. No known copyright holder.

Cushman, Rivers, and Jones—not yet linked in terms of being a combination (a joint act)—continued to appear on the same bills for various dime museums, particularly in the Boston area, across the spring and summer of 1887, culminating in an appearance at the Austin & Stone Museum and Theatre in Boston in September 1887 [31].

Within two months of that performance, all three were in England.

Corlene Cushman, Josie Rivers, and Ike Jones made their English debut in November 1887 at the Comedy Theatre, Manchester, as members of the “Kennedy and Rand Mississippi Jubilee Singers” [32]. Why England? And how had they come to be travelling together?

The answer to the first question may lie once more with Ike Jones’ connection to Billy Kersands. It is likely that Jones had heard from Kersands how Haverly’s Minstrels had been received on their 1881–1882 tour of England. England stood on top of an empire founded on the idea of white supremacy—it was no paradise for people of colour; however, it was also not segregated, and African American stars like Elizabeth Greenfield, the Fisk Jubilee Singers, and, as we have seen, the Bohee Brothers performed for royalty. In addition, and frankly, anything was better than dime museums. I have been unable to find any information on “Kennedy and Rand”, but based on their recruitment of performing artists direct from the US, it is likely that they were either American themselves or had contacts in the US. Regardless, it is clear from the relative billing of Cushman and Jones, both in the US and in the Mississippi Jubilee Singers, that any offer of work would have been made to her rather than Jones. In that light, it can be seen as ultimately her decision to relocate to England, although influenced by Jones’ knowledge of the Haverly experience.

As to how Cushman, Jones, and Rivers came to be travelling together? We know that at some point Cushman and Jones became a couple, perhaps even a legally married couple—they certainly described each other as husband and wife. It is reasonable to fix this development to their time on the dime museum circuit. In other words, they came as a package. We also know that Corlene Cushman described Josie Rivers as her “daughter” to the English newspapers [33]. Although this may have simply been to avoid awkward questions as to why a young child was travelling with two adults who were not her parents, it may equally reflect the way that Cushman, who would have been 35 in 1887, felt towards the 10-year-old Rivers. It is almost certain that they had a mentor–student relationship when it came to singing, something that is evident from Rivers’ later life (although she started as a serio comedienne, by 1908, she was being described in the press as a “soprano” [34]). As can be seen from the quote above from their time in the dime museums, and as would become a feature of their time on the English stage, Cushman and Rivers were often singled out for praise in reviews of the shows in which they appeared. It is easy to see how Cushman might have watched from the side of the stage as Rivers performed and seen her potential—or how Rivers might have been the one at the side of the stage and aspired to become the sort of singer that Cushman was. They would have gravitated toward each other. Again, it is fair to ask where Rivers’ parents were when the decision was made to allow her to travel overseas in the company of two adults who were not related to her by blood; but, also, again, this was not unusual for the time. We can at least be sure that Rivers went willingly and with (to some degree at least) her parents’ consent as she continued to perform under her own name. It is possible and perhaps likely that the arrangement included Rivers making use of the relatively new innovation of “telegraphic transfer” (wire transfer) to send money home to her family.

Although the “Mississippi Jubilee Singers” name was clearly in imitation of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, as with many of the latter’s imitators, rather than being an a cappella vocal group, the Mississippi Jubilee Singers were a minstrel group presenting a mix of song, dance, and comedy simply trading on the fame of the name. This may have been a mistake, as reviews in the press were savage, deriding the vocal talents of the majority of the troupe.

““America’s Greatest Company of Genuine Coloured Vocalists,” if we can believe the programme announcement, hold the Comedy’s stage this week. We cannot believe the programme announcement without thinking rather meanly of America. ”

Once again, it was Cushman and especially, Rivers who elicited the most praise.

“Miss Carline Cushman sang some songs with admirable taste […] Little Josie Rivers was perhaps the most popular artiste of the evening. She possesses a voice of remarkable power for a child, and her character songs made a host of friends in the audience. ”

Jones, who also performed, as would become usual, was not mentioned at all.

Whatever Kennedy and Rand had in mind for their troupe, it could not survive its poor debut and folded within weeks. Cushman, Rivers, and Jones were thousands of miles from home and out of work. But not for long.

“Direct from America, and first appearance in Bolton of JOSIE RIVERS, the Wonderful Child-Character Variety Artiste. First appearance in Bolton of LUKE JONES, Descriptive and Motto Vocalist. First appearance in England of “The Great American Coloured Prima Donna” Miss CORLINE CUSHMAN, the “Black Swan” Soprano Soloist. ”

Setting aside the spurious claim that this was Cushman, Rivers, and Jones’ first appearance on the English stage, “Luke” would appear to be a corruption of “Ike”, suggesting either unfamiliarity with this shortening of “Isaac”, or someone having bad handwriting (Isaac would also be billed as “Jake Jones” for a short period [38]). Of more significance, this ad from the trio’s appearance at a Bolton variety theatre in January 1888, a few weeks after the “Mississippi Jubilee Singers” folded, shows that the three had not yet settled on a firm billing. This suggests that they had not planned to tour independently of the Kennedy and Rand troupe. It would be another six weeks before the three would first perform as the “Black Swan Trio”, [39] but once they had settled on this formula, it became their primary billing for the next six years. Thus, in the space of less than a year, the three had gone from three disparate performers on the bills of dime museums across the US to a unified whole—personally and professionally. The extent to which this was the case is demonstrated by what happened next in their careers: their recruitment by the Bohee Brothers.

The story of the Bohee Brothers falls outside the scope of this work. However, of relevance to us here, as stated above, James and George Bohee arrived in England in 1881 as members of the Haverly’s Mastodon Minstrel Troupe alongside Billy Kersands, and when the troupe returned to the US in 1882, they decided to stay. At James’ initiative (as was usually the case), they opened an “American Banjo Studio” in Leicester Square, where James would give lessons to students, who would grow to include the great and the good of London including Prince Louis, the future King Edward VII. They also performed as a duo at private homes, concert halls, and variety theatres in the London area. They settled into a respectable and outwardly prosperous existence—which, alas, came crashing down six years later, when in early June 1888, George was declared bankrupt due to gambling debts [40].

Bohee Brothers American Banjo Studio ad, Lady’s Pictorial, 21 October 1882. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

George’s debts left the brothers needing to greatly increase their income. So, they went back on the road, touring the country with what was initially a small combination of only six other performers. The Black Swan Trio was included in that number. Critically, the Black Swan Trio, although performing as part of the Bohee combination, also retained their own separate billing, i.e., also formed a separate act as part of the same bill [41]. As we have seen, this remained the case even after, later in the year, James Bohee reformed the combination into a large minstrel troupe. The extent of the role that Jones’ former membership of the Kersands Minstrels played in bringing about this union is unknown. It certainly cannot have hurt the Black Swan Trio’s chances that both Cushman and Jones had appeared on the same bill as the Bohees’ old comrade in the Haverly Minstrels. Given the Bohees’ situation going into their first tour, it is easy to see that Cushman, Rivers, and Jones held a strong hand in the negotiations: the Bohees were much more famous, but they had an urgent need for African American talent that met James’ exacting standards. Cushman, Rivers, and Jones met the bill.

Just how canny James’ eye was for talent can be seen from the reviews of the performances of this first incarnation of what would become the Bohee Royal Minstrels/Bohee Operatic Minstrels, such as this one from a performance in Leinster in July 1889.

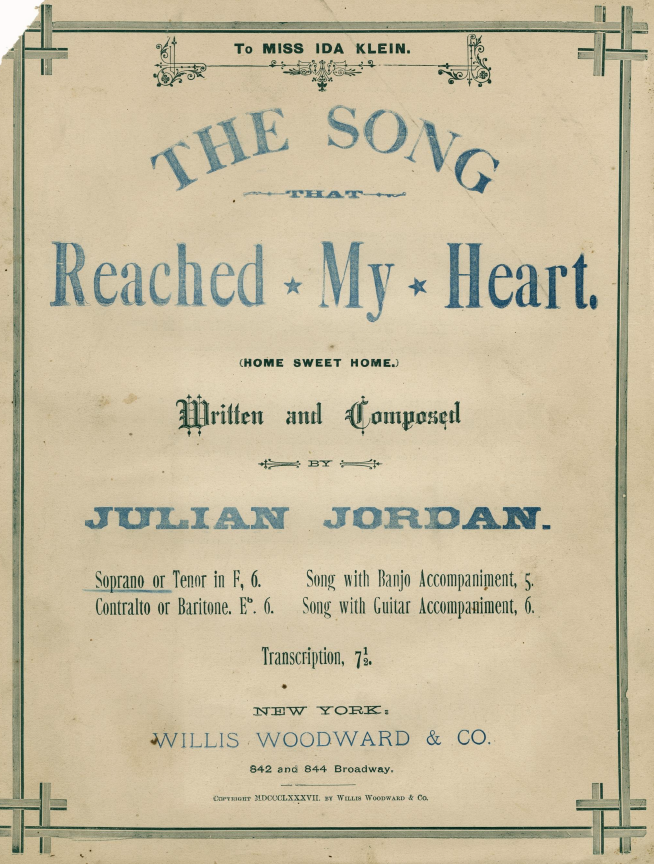

“Miss Cushman received a deserved encore for the ballad, “the song that reached my heart.” Miss Cushman was also very warmly applauded for her rendition of “the Nightingale.” Miss Josie Rivers, a very promising young lady, was very warmly applauded for her rendering of the ballad, “No one like mother” and for a serio-comic song entitled “you’re born, but you’re not buried yet”. ”

University of Wisconsin Digital Collections (UWDC). “Song that Reached my Heart”: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AOVUUC56JKYWRT8U; “No One Like Mother To Me”: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/ACJFOWV4OCBVKG8T.

“The Song that Reached My Heart” and “[There is] No One Like Mother [To Me]” were sentimental ballads, the former by Tin Pan Alley songwriter Julian Jordan and the latter by a writer named Charles A Davies, both sung from the point of view of someone “in a foreign land” thinking wistfully of their family and loved ones “o’er the sea”. Both songs were popular with minstrel troupes for that reason [43].

One thing that is worth noting here is the lack in the troupe’s repertoire at this stage in its existence of “plantation songs”—songs sung from the point of view of “happy slaves”, the bread-and-butter of blackface minstrel troupes and solo performers, male and female alike. This would soon cease to be the case, however, as, within a few years, the troupe’s advertising would boast that its performance realised “the happy plantation life of the Old Southern States” [44], emphasising once again that despite involving real artists of colour whose lived experience included knowing the reality of plantation life, even if only from the stories that their parents told, to continue to appeal to its audience, the troupe was forced to include the stereotypes that the ‘blackface’ troupes embraced, namely, the “sambo” and “coon” characters, the former the “happy slave” of the plantation songs, the latter, the happy-go-lucky but workshy buffoon of the comic sketches [45].

The extent to which James Bohee, in particular, was sensitive to the expectations of the audience can be seen in a court case that dates from the time when the Black Swan Trio were with the troupe that also demonstrates how precarious the reputations of female stage performers, in general, and black female stage performers, in particular, were in England in this period.

By the summer of 1889, the Bohee troupe had expanded far beyond its original six members, and in the June of that year, it expanded still further with the hiring of an African American singer with the stage name of “Nelly Shannon”, who had toured as a solo artist under the billing the “American Coloured Nightingale”. An Ohio native, real name, Sweet or Olmsted, and aged only 20 in 1889, Shannon would go on to have a substantial career on the English stage most notably as a featured performer in touring productions of theatrical versions of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and similarly themed works (“The Octoroon” [by Boucicault], “The White Slaves”) [46]. However, she lasted all of one week with the Bohee Minstrels, falling foul of the strict rules that James Bohee had put in place to safeguard the reputation (and by extension, income) of the troupe.

Shannon was sacked alongside a long-time member of the troupe, Maria Ewing, for being seen drinking in a public house and walking in public with a white man in direct contravention of the rules of the troupe. This information is contained in the suit for unpaid wages (25 shillings a week) that Shannon and Ewing filed against James Bohee. The case—featuring it should be noted, black plaintiffs and defendants—was heard in Southport County Court in late July 1889. In his evidence, George Bohee, who was in court in place of his brother, said that these rules were posted in the dressing rooms for all the artists to see (which rather begs the question: was being able to read and write a condition of their employment?). Ultimately, the court ruled in the Bohees’ favour. In delivering his judgment, the judge, tellingly, said that “it was most desirable that these young women not be seen in public-houses or with white people at night.” [47]

Racial tolerance in England went so far and no further; James Bohee was acutely aware of this and made sure his performers knew it too. Viewed in this light, the readiness with which Cushman, Jones, and Rivers made available the information that they were a family unit (wife, husband, and child) can be viewed as advertising their respectability in the face of public suspicion of the morals of stage performers, in general, and black female stage performers, in particular. The fact that this was at best true in intent only simply demonstrated that this was part of their staged identities that served a dual purpose.

Advert, Era, 1 March 1890. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

The Black Swan Trio toured with the Bohees from June 1888 until March 1890 and then went solo [48]. For the next four years, they would follow a busy schedule of touring the halls as a regular variety act (rather than an element of a minstrel show), clients of Richard Warner and Company, one of the biggest theatrical agencies in the country, who specialised in representing combinations and troupes rather than solo artists [49]. They could even boast of being fully booked for the years 1892 and 1893 [50]. The only known photograph of the trio together (see above) dates from this period of their career [51]. It shows Cushman, Jones, and Rives, aged 40, 32, and 15, respectively, dressed to the nines in the height of—respectable—upper-class fashion. It makes plain that the image that the trio was trying to project aligned with the idea that they were a classical singing trio in the European tradition—very much the prima donna and her husband, the baritone, and daughter, the soubrette. And it is noticeable that their billing in this period describes them as singers of “harmoniously rendered songs, trios, and duetts [sic]”. However, at the same time, there was no denying audience expectations, and “quaint plantation melodies” were also a part of their repertoire [52].

The final thing to note from the photograph is that Cushman has her hand resting lightly on the seated Jones’ shoulder, a chaste but intimate gesture that reinforces the message that this is a family group—and indeed, viewed without context, this could be taken as a studio portrait of a prosperous African American family of the period—an image of respectability a million miles away from the popular view of female performing artists of colour that so troubled the Bohees.

“The Black Swan Trio will return to London on Monday, after a successful twenty-four weeks’ tour”. ”

Just how grueling their touring schedule was can be demonstrated by looking at their engagements for 1894—the last year of Corlene Cushman’s life. In January, they played Portsmouth, Liverpool, and London. After a month of engagements in the London halls, by March, they were in Plymouth. Then, it was back to London for another six weeks of engagements across the capital. Following a quiet June, they were back on the road again in July, in first Sunderland and then right at the other end of the country in Bristol before returning to London. In August, it was Nottingham and the London halls once more. They then returned to the North East in September, for engagements in Newcastle, South Shields, and Hartlepool, before heading north to Scotland for engagements in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Edinburgh again in October. They began November with another week of performances in Edinburgh before moving on to first Birmingham and then Cardiff [54].

It was while appearing in Cardiff in the first week of December 1894 that Corlene Cushman died. She had been unwell for some time with what was revealed after her death to be heart disease (it is not clear if this had been diagnosed before her death). Her cause of death was recorded as morbus cordis syncope [55], suggesting that she would have been subject to fainting spells in the months leading to her death. Crisscrossing the country to perform a nightly vocal act can only have exacerbated the condition and likely shortened her life.

Her name was rendered on the death certificate (Crown copyright) as “Nellie Jones” wife of “Isaac Jones, comedian”. Curiously, when news of her death was reported in the theatrical press, her name was given in some reports as “Bella Cushman” [56].

Nancy (or Sarah or Nettie) Jackson, Caroline, Corline, Corlene, Coraline, or Bella Cushman, and Nellie Jones: she went by many names in the different phases and parts of her life, professional and private. She aspired to a career as a prima donna, inspired by the success of Elizabeth Greenfield, which she may have witnessed firsthand (perhaps even as Greenfield’s student), but, in the early part of her career had to suffer the indignity of performing in dime museums, one of the few opportunities open to the majority of professional singers of colour in the USA at the time. Real success came once she moved to England with her partner/husband and a student she thought of as her daughter, but even there, the demands of the audience meant that this success came at the price of balancing a projected identity as a classical vocalist with a staged identity as a singer of “plantation melodies”. Was she happy? Did she feel fulfilled? We cannot know at this remove. All we can say is that she lived—and died—doing something she evidently loved, singing, in the company of her partner and her surrogate child, and with the approval and acclaim of audiences.

Corlene Cushman was laid to rest in Cardiff New Cemetery (Cathays Cemetery) on 6 December 1894. Her funeral was attended by a large gathering of her fellow performers, and many other artists sent wreaths. She was 42 [57].

A week after the funeral of Corlene Cushman, Ike Jones and Josie Rivers got back to work. The reality was that they did not have the luxury to do otherwise. The Black Swan Trio was booked to appear at venues across Wales, Ireland, and North-West England for the next two months; so that is what it needed to do. Rivers and Jones were joined on stage by a new third member of the trio, a performer by the name of Harry Miller, whose billing as a solo performer was “coloured comedian”, but about whom I know very little else. They finished their contractually obliged commitments in Belfast in the second week of February [58]. Finally, they had time to rest—and grieve—at least for a little while.

“Miss Josie Rivers was, if we mistake not, once with that firm known as the Black Swan Trio, and is now “on her own”, interpreting ballad in expressive fashion and prospering more or less. ”

After several quiet months, Josie Rivers, now aged 18, returned to the stage—alone—in London in May 1895. She continued to appear in various London halls, often on the same bill as Eugene Stratton, the leading blackface performer of the day, across 1895 and 1896, billed as a ballad singer [60]. As for Isaac Jones? He spent much of this period touring with a new incarnation of the Black Swan Trio. This new combination was an all-male affair, probably but not definitely including Harry Miller and a third African American singer. Even more so than the original trio, its repertoire was centred on “plantation songs”, and rather than the sentimental ballads that were the forte of Cushman and Rivers, Jones and his two male partners were described as “glee singers” [61].

This was thus a different beast from the original Black Swan Trio. However, at the same time, Jones cannot be faulted for continuing to use the name. In a world where a booking agent had hundreds of acts in any given genre to choose from, name recognition was of vital importance—that was, after all, why Cushman had called herself the Black Swan. It is interesting to note that this incarnation of the trio even worked with George Bohee for a period, as members of a touring production of the “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” stage play that featured Bohee in a musical interlude and, remarkably, also starred Nellie Shannon—the singer that George Bohee had given evidence against in 1889 after his brother sacked her after only a week [62]. The world of the theatre was a small one, especially for performers of colour in late Victorian England.

It might be supposed from this divergence in the careers of Rivers and Jones that the two, held together by Cushman, had parted after she died. However, this is not the case. For all that they were now leading separate professional lives, their personal lives had become even more entangled, as by 1896, the pair had become de facto husband and wife, and by the beginning of 1897, had had a child together.

Birth certificate, Charles James Benjamin Jones, 1987. Crown copyright.

Josephine Rivers gave birth to a son, Charles James Benjamin Jones (1897–1930), in Everton on 13 February 1897. She is listed on baby Charles’ birth certificate as “Josie Jones formerly Rivers”, wife of “Isaac Jones, Music Hall Artiste”—although there is no record of a marriage, not in England and Wales, at least [63]. The second Black Swan Trio continued to play engagements for much of the rest of 1897—including, as we have seen, as part of a touring production of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”—but was last mentioned in the British press in late October of that year. It is evident that at some point during the year, the decision was made—by Jones? by Rivers?—to return to the USA, as, on 30 November 1897, Jones, Rivers, and their son Charles are recorded on the list of passengers of the SS Gallia, newly arrived in New Brunswick Canada, en route to the USA. This list is one of our only two sources for demographic information for Jones (the other is Charles Jones’s 1918 draft registration). He is listed as 37 and Canadian, born in Toronto. Josie is listed as his wife, and Charles (“Chas”) as his son. They claimed to be travelling on business and gave their final destination as Kansas City, MO [64].

Kansas City, it should be remembered, was where Josie Rivers’ mother, Mary, and sister, Lena, were living; Mary, with her husband of 14 years, William Jacobs, and Lena, recently married herself, with her new husband, Leon H Jordan [65]. Thus, rather than travelling on business, it seems clear that Jones, Rivers, and baby Charles were there to at the very least visit and possibly move in with Rivers’ family.

It is worth stating here that, as far as I can tell from my research, this was the first journey back to the USA that Jones and River had made since they left to join the Kennedy and Rand Mississippi Jubilee Singers in 1887. Given what we know about the Black Swan Trio’s touring schedule first with the Bohee Brothers and then as an independent combination, it seems likely that this was in fact, their first trip home in that time. As to the question of whether this was a visit or a permanent move—at least in intent—it is impossible to tell. What we can say is that it became a permanent move for Rivers and her son, at least. In the case of Isaac Jones, we cannot say, as it is at this point, at least as far as the records can tell us, that he disappears from the lives of Josie Rivers and their son.

Rivers is recorded as Josephine Jones in the 1900 US Federal Census, and their son as Charles Jones; however, they are living with Rivers’ family, not Isaac Jones, and, more critically, 1900 is also the year that Rivers—using her maiden name—married John M Wright of Topeka, Kansas. There is even evidence (see below) that this is the culmination of a courtship that began as early as 1898. Using this information, we can tentatively point to a severing of the relationship between Rivers and Isaac Jones not long after they returned to the USA. This is supported by the fact that although Rivers returned to performing soon after her return to the USA, this was not with Isaac Jones. Instead, in 1898 she joined the touring company of leading African American pianist John William “Blind” Boone.

“Shortly before the close of the entertainment it was announced that if someone would come to the piano and render a selection Blind Boone would repeat it. Miss Ethel Thompson was called for and she responded after which Blind Boone seated himself at the piano, playing the selection exactly as Miss Ethel had done. Miss Josephine Rivers, the singer, is better than the one the company had when here before. ”

John William “Blind” Boone. State Historical Society of Missouri. https://cdm17228.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/imc/id/18377 . No known copyright holder.

John William “Blind Boone” (1867–1927) was, by the first decade of the 20th Century, a leading ragtime pianist—and, indeed, was credited by some people with inventing the form. However, in earlier decades, his performances alongside his own concert company combined European classical and African American spiritual music and were mounted in opera houses, concert halls, and churches. He played to mixed audiences, a rare thing in the USA of the period. Rivers was with the Boone concert company when they played an engagement in Topeka, Kansas, in September 1898 [68], and this is the likely starting point of her relationship with John M Wright, a Topeka resident who was the deputy county clerk for Shawnee County.

These various events in the lives of Jones and Rivers from 1897 to 1890 suggest that whatever Rivers felt about her relationship with Jones when it started, by the time she was back among her family—and had access to an alternative support system for herself and her infant child—she was at the very least content to leave her relationship with Jones behind. It could even be speculated that her taking to the stage separately in England in 1895 was a sign that she was attempting to move away from whatever relationship they had at that point, only for the discovery in mid-1896 that she was pregnant to forestall a full break. However, this is and must remain speculation.

Rivers—using her maiden name—married John Wright in Kansas City in September 1900, and the two moved into the home that Wright had bought for them in Topeka, along with the infant Charles. By 1904, Josephine Wright had graduated with a qualification in music from Washburn College and began work as a music teacher. However, within a few years, she and her husband had instead purchased a movie theatre, and by 1920, Josie was working there as a cashier while Charles was one of two projectionists. By this time, John Wright had risen to deputy county treasurer for Shawnee County [68]. However, this was not to say that Josie Rivers stopped singing, or, indeed, ended her association with the music hall, as in 1908, she attended and gave a performance at the 36th birthday party of Kansas native George Walker, of the Williams and Walker Minstrels fame. She also retained links with England [69].

Charles James Benjamin Jones married in 1919, and by 1927, Josie Wright had three grandchildren, all girls. Alas, tragedy then struck when in 1930, Charles died, aged just 33 [70].

John and Josephine Wright celebrated their ruby wedding anniversary in September 1940 at the home that they now shared with Josie’s mother, Mary Jacobs. However, by the time of their golden anniversary in 1950, Mary Jacobs was gone, and the Wrights had two lodgers [71].

By the time of her death in 1963, aged 86, Josie Wright was a widow. Active in her local church, she spent the last two decades of her life visiting nursing homes and reading to the aged, using her voice to entertain others right until the end [72].

Jamie Barras, March 2025

Notes

ad, Era, 15 September 1888.

The story of the Bohee brothers is told in many places, see, for example: Jeffrey Green and Rainer E. Lotz, "Bohee, James Douglass (1844–1897), musician." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/64724.

This and other aspects of the history of African American versus blackface minstrelsy are explored here: Robert E McDowell, “Bones and the Man Toward a History of Bones Playing. Journal of American Culture”, 1982, 5: 38-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-734X.1982.0501_38.x

The Black Swan Trio can be seen together in a photograph published in the Music Hall and Theatre Review, 25 November 1892.

Julian J Chybowski, “Becoming the ‘Black Swan’ in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield’s Early Life and Debut Concert Tour.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 67, no. 1 (2014): 125–65. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2014.67.1.125. Julia J Chybowski, “Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield’s Mid-to-Late Career, Philanthropy, and Activism in Nineteenth-Century America.” American Music 40, no. 2 (2022): 211–44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48738182. Some critics thought that Greenfield was either a white man in ‘blackface’ and women’s clothing or a genuine woman of colour satirising white prima donnas, i.e., a comedy act. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield (ca. 1824-1876)." New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 18, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1005e100-c5f5-012f-d504-58d385a7bc34.

“Black Prima Donnas of the Nineteenth Century.” The Black Perspective in Music 7, no. 1 (1979): 95–106. https://doi.org/10.2307/1214431. Josephine Wright. “Black Women and Classical Music.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 12, no. 3 (1984): 18–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40003932.

C Robert Tipton, “The Fisk Jubilee Singers.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 29, no. 1 (1970): 42–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42623128. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "Fisk jubilee singers" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 18, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/171daed0-c606-012f-07b3-58d385a7bc34.

Sandra Graham, “On the Road to Freedom: The Contracts of the Fisk Jubilee Singers.” American Music 24, no. 1 (2006): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/25046002.

New York Freeman (New York, N. Y.), 29 May 1888.

‘Amusements’, Montreal star, 2 November 1883.

Edward Le Roy Rice, “Monarchs of Minstrelsy”, (New York: Kenny Publishing Company, 1911),168–243. Frank Cushman in Montreal: ad for Academy of Music, Montreal Star, 12 May 1883.

The marriage of Mirian Jackson and William B Keyes: New York State, Marriage Index, 1881-1967, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc, accessed 20 Mach 2025. A report of “Phebe” Jackson’s death appeared in Era, 21 February 1891. The Utica, New York location also comes from this report. Cushman’s year of birth is based on her age at the time of her death (42) in 1894. Copy of certified death certificate for “Nellie Jones”, Cardiff District, December 1894; copy obtained from General Registry Office, UK, March 2025.

Entries for Phoebe Jackson, Sarah Jackson, and Marion/Marrian Jackson in Utica, Oneida, New York, U.S., State Census, 1860, New York, U.S., State Census, 1865, 1870 United States Federal Census, and New York, U.S., State Census, 1875, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc, accessed 20 Mach 2025.

See Note 13 above.

See Note 5 above, second reference.

‘Great Patti’ billing: ad, Inter Ocean (Chicago, Ill.), 18 March 1884. The earliest use of the ‘Black Patti’ billing for Sissieretta Jones dates from 1888: ‘To Invade the West Indies’, New York Times, 1 August 1888. It is attributed to her manager,

‘Grand opera house’: ‘Amusements’ Saint Paul globe (Saint Paul, Minn.), 29 June 1884. Educated in Europe: ‘Dime Museum’, Inter Ocean (Chicago, Ill.), 19 July 1884.

Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, 11 October 1884.

A H Saxon, “P. T. Barnum and the American Museum.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 13, no. 4 (1989): 130–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40257964.

‘Amusement in Variety’, Boston globe (Boston, Mass.), 8 June 1886.

See Note 17 above.

This information can be reconstructed from the listing for Mary Jacobs, William Jacobs, and Josephine Jones in the 1900 US Federal Census for Kansas City, Missouri, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 26 March 2025. It is worth stating here that the census lists Mary Jacobs as having been married for 26 years, i.e., since 1874; however, William Jacobs would have been only 11 years old in 1874; thus, the 17 years of marriage, i.e., since 1883, listed in his entry is far more likely to be correct, and consistent with the surnames of Lena and Josie (Rivers).

The full essay can be read here: https://agapeta.art/2023/04/14/the-cult-of-the-child-by-ernest-dowson/, accessed 19 March 2025.

This is information contained in her obituary, Kansas City star, 15 September 1963.

‘Amusements’, Inter Ocean (Chicago, Ill.), 16 August 1887.

Ad for Broadway & Treyser’s Palace Museum, St Louis post-dispatch (St Louis, MO), 20 February 1887.

This information can be derived from the entry for ‘Ike Jones’ in the passenger list for the SS Gallia, which arrived in Canada on 30 November 1897, U.S., Border Crossings from Canada to U.S., 1895-1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com, Inc., accessed 19 March 2025. He is described in the list as a ‘music hall artiste’.

‘Colored baritone’: see Note 22 above. Member of Kersands’ Minstrels: this is stated in the ad for Broadway & Treyser’s Palace Museum, St Louis post-dispatch (St Louis, MO), 12 February 1887, and can be supported by the reference to an “I Jones” being a member of the troupe in ‘Amusements’, Buffalo courier (Buffalo, NY) 2 June 1885.

See, for example, this review of a Haverly’s troupe performance: ‘Haverly’s Minstrels’, Aberdeen Evening Express, 28 February 1882.

See Note 14, first reference.

Ad for Austin & Stone’s Museum and Theatre, Boston Sunday globe, 11 September 1887.

‘Comedy Theatre’, Manchester Evening News, 8 November 1887.

Ike Jones, “husband”, and Josie Rivers, “daughter”, of Corlene Cushman: ‘Green-room Gossip’, South Wales Echo, 8 December 1894.

‘George Walker’s Thirty-Sixth Birthday’, Freeman (Indianapolis, Ind.), 22 August 1908. This is the George Walker of the Williams and Walker Minstrels: Stephanie Anne Johnson, “George Walker (1873-1911)”. BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/walker-george-1873-1911/, accessed 20 March 2025.

‘Comedy Theatre’, Manchester Courier, 8 November 1887.

See Note 33 above.

Advert for Victoria Variety Theatre, Bolton, Cricket and Football Field, 28 January 1888.

For example, ‘Gaiety Theatre’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 19 June 1888.

The name first appears in the UK press recording the trio’s appearance at a benefit concert for music hall chairman Gus Leach at the Middlesex Music Hall, London: ‘Mr Gus Leach’s Benefit’, Era, 17 March 1888.

Bohee Brothers. Banjo studio: ad, Lady Pictorial, 21 October 1882. Appearances in the London area, see, for example, ad for the London Pavilion, London and Provincial Entre’acte, 12 October 1882. George’s bankruptcy proceedings: ‘Failure of One of the Bohee Brothers’, Evening News (London), 7 June 1888.

Bohee Brothers and Black Swan Trio both appearing on the same bill: ‘Gaiety Variety Theatre’, Era 23 June 1888. Black Swan Trio said to be part of Bohee Brothers combination: ‘Moss Varieties’, Era, 30 June 1888.

‘The Bohee Minstrels’, Irish Evening Times, 2 July 1889.

The sheet music for both songs can be accessed via the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections (UWDC). “Song that Reached my Heart”: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AOVUUC56JKYWRT8U; “No One Like Mother To Me”: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/ACJFOWV4OCBVKG8T. The latter can also be heard via recordings at archive.org, e.g., https://archive.org/details/78_the-song-that-reached-my-heart-home-sweet-home_evan-williams-julian-jordan_gbia0234092a, accessed 23 March 2025.

‘Weddings, Entertainments, etc.’, Isle of Wight County Press, 17 June 1893.

David Pilgrim, ‘The Coon Caricature’, https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/coon/homepage.htm, accessed 23 March 2025.

Nellie Shannon. Age in 1889: based on her age in the 1901 England Census (32), entry for Ellen Shannon, American Actress, Everton district, accessed ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc, 10 March 2025. ‘American Colored Nightingale’: ad, Crown Music Hall, Derby Daily Telegraph, 28 March 1888. ‘Sweet’: ad placed by Nellie Shannon to trace her mother, Jennie Sweet, ‘Lost Relatives’ Column, Freeman (Indianapolis), 4 February 1893. ‘Olmsted’: 1900 US Federal Census entry for ‘Jennie Sweet’, Columbus, Ohio, which shows that Sweet has a son named ‘Benj Olmsted’ and married her current husband, Joseph Sweet, in 1876, seven years after ‘Nellie Shannon’s birth, accessed ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc, 10 March 2025. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Octoroon, and The White Slaves: Londonderry Opera House listing, Era, 20 May 1893. It is with some irony that I can report that George Bohee would eventually also join the “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” touring company.

Accounts of the case can be found here: ‘A Banjoist in Court’, Era, 20 July 1889; ‘Coloured Artists and Their Conduct’, Guardian (Newcastle), 20 July 1889.

The Black Swan Trio announced the end of their engagement with the Bohees in an ad in the Era,1 March 1890.

Charles Douglas Stewart and A J Park, “The Variety Stage” (London: T Fisher Unwin, 1895), 129–131.

Ad, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 16 September 1892.

See Note 4 above.

Ad for the Empire Palace, Portsmouth, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 5 January 1894.

‘Music Hall Gossip’, Era, 20 January 1894.

This list was assembled from a search of britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk for “Black Swan Trio”, filtered for 1894 and then reviewed week by week, accessed 25 March 2025.

Certified death certificate for Nellie Jones, wife of Isaac Jones, Comedian, 3 December 1894 , Cardiff district, obtained from the General Registry Office, March 2025. Cushman is described as having been “ailing for some time” in, for example, South Wales Echo, 8 December 1894.

Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 22 December 1894.

See Note 54 above, second reference. It is in this report that Rivers is described as “the daughter of the deceased”.

The Black Swan Trio honoured an engagement at the Empire Theatre, Newport that began 10 December 1894, four days after Corlene Cushman’s funeral: ‘Empire Theatre, Newport’, Era, 15 December 1894. Harry Miller first appears as a member of the Black Swan Trio in a review of their Newport performance: ‘Empire Theatre, Newport’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 14 December 1894. Final performances before hiatus: ad for ‘Alhambra Theatre of Varieties’, Northern Whig, 8 February 1895.

‘Marylebone’, London and Provincial Entre’ Acte, 16 November 1895.

Ad for London Variety Theatre, Shoreditch, Entre’ Acte, 18 May 1895.

New Black Swan Trio touring the North West of England: ‘Bolton – the Grand’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 7 June 1895. ‘Birkenhead – Argyle’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 13 December 1895. Three male singers (“trio of plantation boys”): Era, 23 October 1897. Jones and likely Harry Miller: ‘Sadler’s Wells Theatre’, Entre’ Acte, 2 May 1896. Glee singers: ‘Margate’, Thanet Advertiser, 10 July 1897.

Advert for “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, Era, 15 May 1897.

Certified copy of the birth certificate of Charles James Benjamin Jones, born 13 February 1897, Everton, birth registered 24 March 1897, West Derby District, copy obtained from the General Registry Office, March 2025. The Black Swan Trio were playing Liverpool that month. Evidently, Josie Rivers/Jones was travelling with her husband: ‘Amusements in Liverpool, the Westminster’, Era, 20 February 1897.

Listing for ‘Ike Jones’, passenger list, SS Gallia, arrived New Brunswick, 30 November 1897, U.S., Border Crossings from Canada to U.S., 1895-1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 26 March 2025.

See Note 22 above. Lena Jordan was staying with her mother and stepfather at the time of the 1900 US Federal Census. The name of her husband (Leon H Jordan) can be found in the General Index to Marriages for Jackson County, at Kansas City, Missouri, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 26 March 2025.

Springdale News (Springdale, Ark.), 17 February 1899.

University of Central Missouri History Department Dr. Jon E. Taylor , “Blind Boone's Warrensburg Experience Blind Boone Concert Company,” Historic Missouri, accessed March 26, 2025, https://historicmissouri.org/items/show/60. It should be noted that this article states incorrectly that Josie Rivers toured with Boone in 1896 and 1897. Josie Rivers performing with Blind Boone in Topeka, Kansas: ‘Snap Shots At Home News’, Topeka State Journal (Topeka, Kan.), 27 September 1898.

Marriage license for John M Wright and Josephie M Rivers, Jackson County, Missouri, U.S., Marriage Records, 1826-2014; graduating from Washburn College: ‘Out at Washburn, Topeka State Journal (Topeka, Kan.), 15 June 1904; music teacher: entry for Josephine Wright, Topeka, Kansas, Division, 1910 US Federal Census; bought a movie theatre: US Draft Registration for Charles James Benjamin Jones, 1918; Josie and Charles working at theatre and John Wright deputy treasurer: entry for Josephine Wright, Topeka, Kansas, Division, 1920 US Federal Census.

George Walker: see Note 34 above. Josie Rivers (‘Mrs John M Wright of Topeka’) singing at his 36th birthday party: ‘George Walker’s Thirty-Sixth Birthday’, Freeman (Indianapolis, Ind.), 2 August 1908. Links with England (receiving a letter from there): ‘Snap Shots At Home News’, Topeka State Journal (Topeka, Kan.), 16 October 1914.

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/details/GMY4-358, accessed 27 March 2025.

entry for Josephine Wright, Topeka, Kansas, Division, 1940 US Federal Census, and entry for Josephine Wright, Topeka, Kansas, Division, 1950 US Federal Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 26 March 202.

Obituary: see Note 24 above.