Cuckoos and Nightingales

Jamie Barras

Trigger warning for quotes from period sources that contain what today are considered slurs

Prelude: Crows

“The Largest Troupe of REAL NEGROES AND FREED SLAVES That Has Ever Travelled This Country will introduce Songs, Choruses, Banjo, Tambourine, and Bone Solos, representing Plantation Life in their Native Home.”

“Tom shows”—dramatisations of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” with added musical interludes [2]—were so popular in late-Victorian England that there was even an instance of the same production with the same cast running simultaneously in two theatres with performances in one theatre beginning as soon as the cast could make their way over from the other theatre at the end of performances there [3].

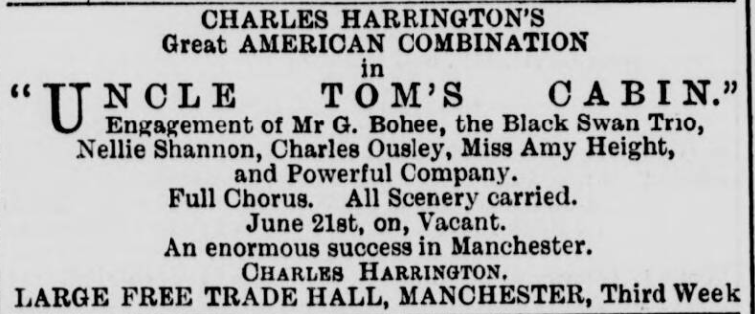

Although the latter was something of an extreme case, it was common for different—competing—productions to be playing at the same time in different parts of the country. Such was the case in 1892 when a Charles Harrington-produced version toured the provinces at the same time as a version written and produced by Charles Hermann was playing in London [4]. In common with most Tom shows, both productions mixed dramatised scenes from the anti-slavery novel with musical entertainment that presented a paradoxically rosy view of life on an antebellum Southern plantation.

In both productions, the character of the young enslaved African American girl Topsy was played by an actress called “Nellie”—Nellie Shannon in the case of the Harrington production, and Nellie Christie in the case of the Hermann production. However, the performances by the two actresses received very different reviews, with Shannon being praised for producing a performance that was “thoroughly droll, real, and convincing” while Christie was decried for indulging “to the fullest extent in eccentricities which grotesquely caricature Mrs Stowe’s original character” [5].

The disparate talents of the two actresses aside, there was something else that separated them: Shannon was a woman of genuine African American heritage born in Ohio, while Christie was a white woman born in Hammersmith [6].

In this article, I will look at the history of Tom shows in England to show how English audiences’ embrace of the comforting fiction served up by blackface minstrelsy shaped not only the shows themselves but also the staged identities of the performers like Shannon and Christie caught in their orbit.

The first stage productions of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” to be mounted in England appeared within months of the May 1852 publication of the book’s first English edition, with three different and competing versions launching within weeks of each other in September of that year at the Standard, Victoria, and Olympic Theatres in London [7]. These were not yet Tom shows, however, but “straight” plays: simple dramatisations of the text, albeit with white actors in blackface playing the roles of the enslaved characters, and sometimes substantial changes to that narrative—in the version that played at the Olympic, for example, written by the prolific writer of melodramas Edward Fitzball, the whole sequence involving Simon Legree was dropped; Fitzball instead had Tom and Harry repurchased by Shelby after the death of St Clare, allowing Tom to survive to be freed along with the rest of the Shelby family slaves to give the play a happy ending [8].

Illustration of 1852 production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in London, Illustrated London News, 2 October 1852. Author’s own copy.

These early productions did, however, already contain what would become a key element of the Tom shows of later decades: preludes or entre’actes that showed spuriously bucolic scenes of “plantation life”; all that was missing was the happy slaves thus portrayed bursting into song and dance. That they did not do so is in one sense remarkable, not only because songs were a feature of American productions of the play from the very first but also because these scenes drew directly from a staple of the English stage in this period, so-called “Ethiopian operas” [9].

“A quintet of Ethiopian minstrels, named German, Stanwood, Harrington, Pell, and White have arrived in England […] Two strum on the banjo, another has the accordion, and the two others play the tambourine and the bone castanets.”

Virginia Minstrels (source: [11])

The history of blackface minstrel troupes (as opposed to ‘Jim Crows’—solo blackface performers) begins in 1843 with the more or less simultaneous emergence in the Northeastern United States of Pell’s Ethiopian Serenaders, the Virginia Minstrels, and Christy’s Minstrels [11]. All three troupes were initially of the same basic form: four to six white male performers in blackface make-up and evening clothes standing or sitting in a semi-circle and consisting of one or more banjo players, an accordionist or fiddle player, and, anchoring either end of the line, a tambourine player (“Tambo”) and a player of the “Bones”, a percussive instrument consisting of wooden or animal bone strips held between the fingers and struck together much like, as the quote above makes plain, castanets [12]. In time, “plantation dances” would be added to the mix, laying the foundations for the full “Ethiopian operas” of later decades. Pell’s Ethiopian Serenaders, who, like the Virginia Minstrels, first toured England in the same year they were formed, 1843, would on later tours, be joined by a young African American dancer with the billing “Ceda” or “Boz’s Juba” (Willian H Lane, 1825(?)–1853(?))—“Juba” being the name of the dance style that Lane executed [13].

However, it was Christy’s Minstrels who did most to perfect what would become the template of the blackface minstrel show, a three-act performance that began with songs, dances, and comedy skits centred on the minstrel line anchored by Tambo and Bones, then moved on to a more or less conventional variety bill, with, for example, singers, comedians, dancers, and ventriloquists (all in blackface) appearing one after the other, before ending with musical entertainment that presented an entirely spurious picture of the happy, carefree life of slaves on southern plantations—the “Ethiopian opera” element of the performance.

After a successor troupe to the original Christy’s Minstrels, still using the name (much to the chagrin of the titular Christy), toured England in 1857, this template was copied by so many other blackface troupes that “Christy Minstrels” became a general descriptor of this type of entertainment in England [14]. To the Christy troupes can also be attributed the popularisation of the two prototypical blackface minstrel characters, the name of one of which is now regarded as a slur; these are the “dandy”—the articulate “man about town” who served as the interlocutor and straight man; and the “coon”—the happy-go-lucky ne’er-do-well and source of much of the comedy. The appeal of the “coon” character was such that even more so perhaps than “Christy minstrel” the word became a shorthand description of this type of entertainment [15].

There was one more development in blackface minstrelsy that contributed to the birth of the Tom shows that we need to consider, and that is the emergence of blackface minstrel troupes formed of genuine performers of colour. We must first, however, distinguish between black performers of blackface minstrelsy and black performers of other forms of musical entertainment.

“MISS GREENFIELD (the BLACK SWAN), accompanied by Sir George Smart, had the honour of singing some of her national songs to Her Majesty yesterday, at Buckingham Palace.”

A year after the publication of the first English edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the “Black Swan”, African American prima donna Elizabeth Greenfield, toured England, performing songs from the European classical canon. As I have written elsewhere [17], Greenfield’s example was followed by a number of other female solo singers of colour, and, as we will see, some of these performers eventually found themselves drawn into the orbit of the Tom shows—Nellie Shannon among them.

In a related vein, the emergence of the Tom shows, two decades after the Black Swan toured England, coincided with the creation of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a co-ed a cappella group that sang both songs from the European classical canon and what were termed at the time “slave songs” (spirituals). That the entertainment that performers like Greenfield and the Fisk Jubilee Singers offered was distinct from that of blackface minstrel troupes—at least, at its inception—is made plain from reviews of performances by the Jubilee Singers, many of whose songs had rhythms unfamiliar to English audiences.

“The chairman remarked on the weird-like singing of the vocalists, and said it was nothing like the parody presented the English people by the Christy Minstrels and other burnt-cork negro singers.”

I have written about this aspect of Nineteenth-Century English musical entertainment elsewhere [19], but of relevance to us here is that, once imitators started to appear, the lines that separated this type of performance from that of blackface minstrel troupes began to blur, both because minstrel groups simply started calling themselves “Jubilee Singers” without otherwise altering their acts, and because African American a cappella choirs who followed the Jubilee Singers to England found that English audiences would only warm to their performances when sugared with minstrel-esque elements—“plantation” songs. African American a cappella choirs would in time become a major source of performers, particularly female performers, for Tom shows.

The reluctance of English audiences to embrace authentically African American musical forms [20] may explain why, somewhat paradoxically, the first troupe of African American performers of blackface minstrelsy to tour England, the “Alabama Minstrels”, copied their act from the blackface Christy’s Minstrels rather than drawing on a genuine African American musical tradition—to the extent that, in their billing, they claimed to be “from 444 Broadway, New York”, which was, in this period, the address of Fellows Opera House, home to the original Christy’s Minstrels [21]. (It is also worth pointing out that at least some of the troupe’s members whose identities we can trace were genuinely from New York [22].)

The Alabama Minstrels first toured England in 1857—the same year that the second-generation Christy’s Minstrels toured the country—and were particularly active in the early and mid-1860s. Reviews make plain how much the troupe owed to Christy’s Minstrels with a line anchored by Tambo and Bones and performances centred on the blackface staple of happy scenes of plantation life. From reviews and advertisements, we can also identify the changing membership of the troupe across the years 1861 to 1867; one constant in these line-ups was the presence of George Hagerman (born in Canada in around 1826), and it seems likely that the troupe was formed and led by him. Other members over the years included T M (or J M) Lewis, John W Waters, John A Johnson, G H Thompson, H W Page, J Holmes, Jules Reviere, Fred Julene, W Diamond, H Brown, and a man named Davis. The similarity of some of the latter names to those of well-known white performers (Jules Reviere/Jules Riviere, W Diamond/Frank Diamond/John Diamond) suggests strongly both that these were stage names and that they were thought up in a hurry, possibly to disguise the fact that in the troupe’s later years, Hagerman employed performers moonlighting from their regular gigs with other troupes [23].

This latter explanation is suggested by the fact that, by 1866, a second African American minstrel troupe had also begun to tour England. Beginning life in the USA as the “Georgia Slave Troupe Minstrels”, but touring England first as the “American Slave Serenaders” and later the “American Slave Troupe”, this group originally of 15 performers was created by white impresario W H Lee in 1865. British music hall performer (and clog dancer) Sam Hague discovered the troupe while on a tour of America, bought out Lee, and brought the troupe to England. The star of the troupe’s original line-up was “Japanese Tommy” (Thomas Dilward) an African American person of small stature. Another member of the troupe was Bob Height (Robert Henry Height, 1846–1881), who would go on to marry an Englishwoman and settle in England [24]. I will return to the life and career of Bob Height later in this article. (Image: Sheffield Daily Post, 18 August 1866. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.)

In time, with the departure of its original members and difficulty in recruiting replacement African American performers, Hague would begin to supplement the troupe’s line-up with white performers in blackface, prompting eventually a change in the name of the troupe to the Hague Minstrels. This process was accelerated by African American minstrel troupe leader Charles Hicks, who had created his own Georgia Minstrels in imitation of the original, poaching some of Hague’s African American performers following a brief period in the early 1870s when the Hicks and Hague troupes toured England and Wales as a single combination.

Once back in the USA, Hicks sold his interest in the Georgia Minstrels to Charles Callender, a famously terrible employer, causing most of the performers Hicks had poached from Hague to leave for pastures new. Billy Kersands, later of Haverley’s United Mastodon Minstrels and then his own troupe, was one of the performers who defected from Hague to Hicks, as were Bob Height and Japanese Tommy; all three would end up leaving Callender’s employ and over time, find themselves back in England [25].

The mixing of black and white blackface performers In the Hague troupe epitomises the extent to which, just like the Alabama Minstrels, the troupe’s performances stuck to the Christy Minstrel template. In the case of both troupes, giving English audiences what they wanted required the performers to ignore their lived experiences and adopt staged identities created by white performers that were inherently caricatures of the African American experience.

This emergence of black performers of blackface minstrelsy in the USA in the 1860s was one of the key drivers of the creation of Tom shows in the following decade, representing, as they did, a pool of performers that the white creators of Tom shows could draw on to lend their productions a spurious air of authenticity (by including what they described in the billing as “real negroes and freed slaves” in the cast). Similarly, Tom shows touring England in the 1870s and beyond would, as we will see, be able to draw on African American and Black Canadian performers already resident in the country due to the popularity of solo artists, Jubilee Singers, and blackface minstrel troupes. All the elements were now in place for a revival of stage versions of the Stowe novel in its new hybrid form.

“A new version of [Uncle Tom’s Cabin], by Messrs. Jarrett and Palmer, as acted at Booth’s Theatre, New York, is now placed simultaneously on the stage of two London theatres […] In addition to a considerable number of American and European artistes, have been imported “a host of genuine freed slaves from the Southern States of America” who appear together in an original plantation festival scene.”

Henry Clay Jarrett and Harry Palmer first found success as a producer team when they mounted what would go on to be a much-mythologised production, “The Black Crook”, at Niblos Garden [theatre] in New York in 1866. Sometimes described, probably erroneously, as the “first Broadway musical”, “The Black Crook” was a musical comedy take on a Faustian pact between an evil count and an equally evil wizard (the “black crook” of the title) thwarted by a pair of young lovers. It was based on an opera bouffe and was, as this synopsis suggests, heavily inspired by a visit that Jarrett and Palmer had paid to a pantomime on a scouting expedition to England the year before. It was also a massive hit helped in no small measure by the, at the time, scandalously skimpy outfits worn by the production’s female dancers [27].

“The Black Crook” had a cast of hundreds, and Jarrett and Palmer wanted their 1878 revival of Uncle Tom’s Cabin to be mounted on a similar scale, which required the hiring of dozens of African Americans as walk-on extras for the “plantation festival” scene, the entertainment for which would be provided by established stage performers of African American heritage—Jubilee Singers and black performers of blackface minstrelsy—and centred on a star turn from a banjo soloist, the most prominent of which in the casts that Jarrett and Palmer brought to England was Horace Weston (1825–1890).

Jarrett & Palmer’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and a portrait of Horace Weston, star banjoist of the original London production. Images courtesy of the Digital Public Library of America.

Jarrett and Palmer were not the first producers to create a Tom show—indeed, they poached many of their African American stage performers from existing Tom shows—but they were the first to conceive of shows on such a large scale. One illustration of this was the fact that they brought two casts to England—one to appear in London and the other to tour the provinces (Weston was in the London cast; the star banjo soloist in the touring company was a performer called Warren Griffen [28]). The performers arrived in England in August 1878 onboard the SS Adriatic and disembarked at Liverpool. Their evident joy at completing the journey was reported in the local press, which also reported that the company was 60 in number, 54 of whom were “negroes, and comprised men and women, boys and girls, and a few children” [29].

Alas, we do not have the passenger list for the Adriatic for this journey. We do know, however, that, as well as including Horace Weston, the London cast included the Richmond Camp Meeting Choir of Virginia led by “leader and shouter” Sarah Washington, the “Louisiana Troubadour Quartet of liberated slaves” (Newman, Stewart, Brown, and Manly) and “The Four Jolly Coons” (Bundy, Clifton, Thompson, and Gaines), all of whom had appeared in the New York production (and earlier Tom shows). Amongst the child performers were brother and sister dancers, the Slidells. The minstrel troupe in the touring company was led by “Primrose” Kelly and included the Sawney children and the “Sable Quintette”, a set-up mirroring that of the London company.

It should be emphasised that all of these performers performed only in the “plantation festival” musical interlude, except for some of the choir members, who provided “mood music” for some of the play’s more maudlin moments—all of the speaking parts, enslaved Africans included, were played by white actors [30].

It should also be said that, as discussed below, some of the above-named performers would stay in England once the Jarrett and Palmer companies returned to the USA and over the next two decades, would turn up again and again in different roles in the many Tom shows that followed the Jarrett and Palmer production onto the English stage. It is also likely that some of the African American and Black Canadian performers who arrived on the English stage fully formed were members of the combinations included in the Jarrett and Palmer tours for whom we do not have names. In this context, we can speculate that the camp meeting choirs/jubilee singers were a source for some of the solo female performers of colour who debuted with increasing frequency in the years following the Jarrett and Palmer tour.

“On Monday and Wednesday, 16th and 18th June, UNCLE TOM’S CABIN, or SLAVE LIFE IN AMERICA. On Tuesday and Thursday, 17th and 19th June, Boucicault’s Great Drama, the OCTOROON, or SLAVE LIFE IN LOUISIANA. In the course of each Drama the JUBILEE SINGERS will sing a variety of their most POPULAR MELODIES.”

Harry Palmer, one-half of the Jarrett and Palmer production duo, died in London in July 1879. By this time, the original London company had embarked on a tour of Europe, while the original touring company continued to play the provinces in the UK. Evidently, the touring company was itself reduced in size at this time, as new Tom shows began to appear boasting of including performers from the Jarrett and Palmer original [32]. One innovation of these new productions that was to become a staple of the form going forward was to pair performances of Uncle Tom’s Cabin with those of Dion Boucicault’s “The Octoroon”.

Written in 1859, “The Octoroon” shared with Uncle Tom’s Cabin a plot involving conflict around slavery on a Southern plantation. However, one important difference between the two works was that “The Octoroon” centred on a “forbidden” romance between a white man, George Peyton, and Zoe, an enslaved woman of colour (the “octoroon” of the title; the term referring to someone of mixed heritage). In American productions, at the play’s climax, Zoe kills herself, recognising that because of their different races, she and Peyton can never be together. British productions, however, had a happy ending, with Peyton and Zoe marrying. This key difference has often been used to describe “The Octoroon” as an anti-slavery play, with its two endings reflecting the differing degrees of acceptance by American and British audiences of miscegenation. However, during his lifetime, Boucicault himself rejected this characterization of his work and ascribed the two endings instead to British audiences’ insistence on a happy ending, something he only reluctantly gave way to as he intended the work to be a tragedy [33].

When paired with Tom shows, “The Octoroon” was given its own musical plantation interlude, turning it into its own Tom show. After 1882, a third play with a racial theme, “The White Slave” by Bartley Theo Campbell, would be added to these bills, again with a plantation interlude. An American take on the plot of “The Octoroon” first produced in New York in 1882, Campbell’s innovation was to have the female protagonist, Lisa Hardin, believe herself to be a woman of colour but actually be white; when this misunderstanding is cleared up at the play’s climax, this leaves Lisa free to marry her white sweetheart, Clay, without fear of miscegenation (the fact that Clay is Lisa’s uncle by adoption is left unexplored). This combination gave audiences three Tom shows spread across a week of performances—or, from the point of view of the financial backers, three shows that could be mounted with a single cast that included both white and black performers [34].

The two most prominent producers of the Stowe–Boucicault–Campbell triple bill in this period were, as we saw at the start of this article, Charles Harrington and Charles Hermann.

Actor, writer, producer, and theatre proprietor, Charles Hermann was the first of the pair to begin staging Tom shows and would do so for over 20 years. He mounted his first production of the play in 1883. Hermann was a real showman, and his gimmick for this first production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (which was not yet paired with other plays—that would have to wait until the following year) was to use real Cuban mastiffs (“slave retrievers”) in the slave-chase scenes. The dogs did not take well to stage direction and frequently attacked the actors and theatre staff, which led eventually to a court case and a (substantial for the time) fine of £40. Hermann—who was himself attacked by the dogs on one occasion—would probably have considered this good publicity [35].

Part I: Nightingales

For the purposes of this article, the most significant innovation that Hermann introduced was the casting of African American actors in speaking roles, most prominently that of the titular character. When Hermann was attacked by his own dogs, it was Bill Edwards, the actor playing Uncle Tom, described in the press as “a powerful negro”, who saved him. Another African American performer in the company caught up in the incident was Bentick Rowe, who would in later years, also play Uncle Tom [36].

Although Edwards would only play Uncle Tom for Hermann for a single season, he would go on to play the role—sometimes for other producers, other times at the head of his own touring company—off and on for the next 15 years, billing himself as “the only original coloured Uncle Tom” to differentiate himself from other actors who followed in his footsteps [37]. However, arguably, it is two of the actors who followed Edwards in the role in the Hermann production who had a greater impact on the African American contribution to English theatre.

The first of these two actors was R B Lewis.

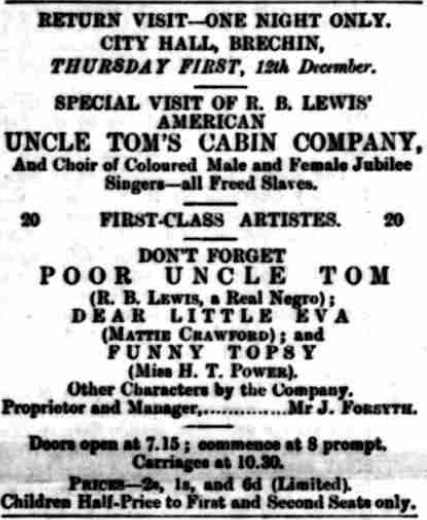

Advert for R B Lewis’s American Uncle Tom’s Cabin Company, 1889. (Source: [38]. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.)

Like Edwards, R B Lewis would only remain with the Hermann company for a single season, but he would go on to play the role for the W T Rushbury company the following year. More significantly, by 1888, he had taken over management of the company from Rushbury and, as “R B Lewis’s American Uncle Tom’s Cabin Company”, would tour the play around the UK halls for the next 8 years [39]. It is probable but not certain that this R B Lewis was the R B Lewis who led African American minstrel troupes on tours of Asia (Australia, New Zealand, India, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, and China) from the late 1870s until the early 1880s It is significant in this regard that, on its 1882 tour of New Zealand, this R B Lewis’s troupe was known as as the ‘Mastodon Star Minstrels and Star Dramatic Company’, and mounted a production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin with Lewis in the titular role [40]. In England, Lewis’s repertoire extended beyond the usual Stowe–Boucicault–Campbell combination to embrace the likes of “Othello”, with Lewis taking the titular role, and the pot-boiler “East Lynne”, with Lewis taking the role of Constable Bullock—his repertoire extended beyond characters of inherent African heritage [41].

Lewis was an actor of range and a man with drive. It is significant, therefore, that Uncle Tom’s Cabin remained a mainstay of the company that he ran—once more showing that this is what English audiences wanted to see. He died in late 1896 or early 1897, probably in Ireland [42]. He was survived by a wife and daughter. Before her marriage in 1897, his daughter, Lena Lewis, appeared in his productions alongside him, taking on the role of little Eva, amongst others [43]. As, to date, I have been unable to determine if Lena Lewis was the natural or step-daughter of R B Lewis, I do not know what, if any, significance can be attributed to her playing the role of a white character. Research into this fascinating character is ongoing.

The actor who followed Bill Edwards and R B Lewis in assuming the role of Uncle Tom for Charles Hermann would also go on to be a significant figure in the African American contribution to English theatre. His name was George C Walmer (1843–1897), and he played the role of Uncle Tom in both Hermann and Harrington productions for a decade, becoming, like Edwards and Lewis, one of the most visible performers of colour on the English stage in this period. He died the same year as R B Lewis, 1897, aged 54. Walmer was said to have himself “experienced the horror of South American slavery”, and there is evidence to suggest that he arrived in England as early as 1875 and worked as a musician before taking the role of Uncle Tom; however, facts about his life before he began performing in Tom shows are frustratingly few [44].

It is, of course, no coincidence that even more so than Bill Edward’s, R B Lewis and George Walmer’s careers on the English stage were built on the same role, and that role was Uncle Tom. This is again indicative of the effect that the popularity of Tom shows had on the career “choices” of African American performing artists caught in their orbit.

Walmer would make a further contribution to the English stage through his marriage to Stephanie Muller, née Schmidt, in 1887, as one of the children they would have together, Cassie Walmer (1888–1980), would go on to have a long career in first, music hall and later, musical revue (the latter using the stage name Janice Hart, in association with her second husband Frank O’Brian) [45]. She is one of several second-generation performers of colour whose careers intersect with this story.

Cassie Walmer’s first stage appearance was in 1892, aged just 3, as one of the enslaved people in the plantation festival scene of a performance of Charles Harrington’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in which her father was starring. As a law had been passed two years earlier banning children younger than 10 from the stage, except under license, this resulted in a fine for her father and Charles Harrington. Walmer and Harrington evidently did not learn their lesson, as they would be back in court 3 years later, alongside another African American artist in the company, Esther Downham, for allowing Cassie Walmer and Esther’s daughter May Downham to perform [46]. I will return to the later career of Cassie Walmer at the end of this piece.

Cassie Walmer. Public Domain

It is worth noting here that Harrington did go to the trouble of getting a license to allow his own daughter—stage name Sylvia Stella—to perform one of the leading roles, little Eva. Sylvia Stella would continue acting in her father’s production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin for close to 20 years, transitioning from playing little Eva to playing Topsy (in blackface) as she grew older, before eventually retiring from acting on her marriage to [her cousin] Henry Harold Halfpenny. Harrington’s wife, the actress Zerlina Zerbini, daughter of violinist John Baptist Zerbini, was also a mainstay of the company. Like her husband, Zerlina Zerbini was an actor and singer in musical comedies and straight plays before the couple “struck it rich” staging the Stowe–Boucicault–Campbell triple bill. Like Hermann, they would continue touring the plays around the country well past the turn of the century [47].

“In the space at our disposal it would be impossible to give a fairly adequate description of the toute ensemble of this decidedly original and clever version of Defoe’s classic work. We cannot, however, omit to mention in eulogistic terms the grace and elegance exhibited by Miss Amy Height in her charming delineation of the character of Topsy, Friday’s squaw.”

The fact that Sylvia Stella played Topsy in Charles Harrington’s version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin is noteworthy, as this alongside Uncle Tom was another role that we know was also assumed by African American performers. Whatever her role in Stowe’s novel, as realised in the Tom shows, Topsy was one of the principal sources of comic relief, and so popular that the character was co-opted by at least one writer of pantomimes (then as now, pantomimes were famous for “borrowing” from other popular works of their time). This is of particular significance to this article, as it is in the role of Topsy as realised in pantomime that we have our first definite evidence of the role being played by a female artist of colour.

Geoffrey Thorne’s new dramatisation of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe opened in pantomime in the Christmas 1886 season. The plot saw not only Crusoe but also his family, his sweetheart Polly Perkins, and his villainous rival for Polly’s affections, Will Atkins, shipwrecked on a desert island, where they were aided in their attempts to avoid being eaten by King Rhumbumbo and his cannibals by not only Friday but also Friday’s “squaw” Topsy. Thorne somehow managed to also fit into this farrago a patriotic pageant celebrating Britain and its empire [49]. The public adored it and—as we will see—this version of the pantomime and others in imitation of it would be revived every Christmas well into the Twentieth Century. The “new” character of Topsy—in reality, copied wholesale from the version in the Tom shows of the period—was played in the inaugural production by African American music hall artist Amy Height.

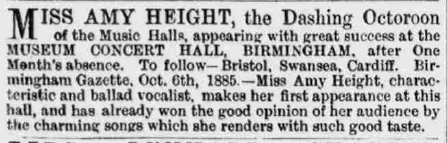

Era, 10 October 1885. Public Domain.

Amy Height (1866?–1913) debuted as a solo performer in early 1883 under the billing “the octoroon songstress” and would go on to have a 30-year career in the halls, appearing in pantomimes, minstrel shows, regular variety bills, and, yes, Tom shows [50]. One thing to note is that, although her career was not restricted to Tom shows and other forms of minstrelsy, the expectations of English audiences were such that, for much of her career, her variety act included “plantation ditties” [51]. In this respect, her career shares similarities with that of artists like the Black Swan Trio, about whom I have written elsewhere [52], and as we will see later, Nellie Shannon.

Amy Height is also something of an enigma, as she gave different accounts of her place and year of birth at different times of her life to different people, including census takers. She was most likely born sometime in the second half of the 1860s, most likely in America; however, based on information she herself provided, her date of birth could have been as early as 1860, and her place of birth, somewhere in England—late in her career, one American admirer who saw her perform in London was even told that she had never been to America [53].

The surname “Height” immediately brings to mind Bob Height, the African American blackface minstrel who settled in England in the early 1870s, mentioned above in connection to the Sam Hague minstrels; and, indeed, in a notice announcing Amy Height’s appearance at the Alhambra, Hull, in December 1892, she was described as the “daughter of one of our old-esteemed corner men, Bob Height” [54].

We know that when Bob Height married his English wife Mary Abbot in Everton in 1874, he was a widower [55]. Putting this together with the information above, we can theorise that Amy Height was a daughter of Bob Height from his first marriage and, following the death of her mother, travelled to England to join him. Growing up in England, in time, she came to see herself as more English than American, particularly when in the company of Americans. However, this is just a theory—there are no records to support it, and even some that challenge it. One issue is that Bob Height died in 1881, yet the first mention we have of Amy Height in England is two years later [56]. Another is that we know that on census night 1881, Bob and Mary Height were together in Edinburgh and there was no one else with the name Height with them [57].

As it seems unlikely that if Amy Height was Bob Height’s daughter, she would have any reason to travel to England after his death, we would need to have some explanation for why she was not with her father and stepmother in Edinburgh in 1881. It is possible that this was because she was at boarding school somewhere—a not-unusual situation with a parent or parents in show business; however, to date, I have not been able to find her in the 1881 census records for England, Scotland, or Wales. Of course, the reason for this may be that the information that Amy Height was Bob Height’s daughter came from Amy herself, and this was just another of her inventions. Research is ongoing.

Regardless of the grey areas in her biography, Amy Height is important to our story not only because of the length of her career in the English halls but also because she connects Nellie Shannon and Nellie Christie—the two performers of the role of Topsy in Uncle Tom’s Cabin—who were introduced at the start of this article.

To take Nellie Shannon first, in 1888, Amy Height joined the first iteration of the troupe of minstrels that the Bohee Brothers, James and George, formed in England. I cover some aspects of the career of the Bohee Brothers, banjo players to royalty, and the history of the minstrel troupe that they toured around the English halls, elsewhere [58]. Of relevance to us here is that Amy Height was one of the featured performers of the first iteration of the troupe—alongside the Brothers themselves and the Black Swan Trio—touring with it from the summer of 1888 until the summer of 1890 [59]. This means she was in the company in the summer of 1889 when soprano Nellie Shannon was hired and fired in less than a week.

“Miss Nellie Shannon, the Topsy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was presented on Saturday night, on the stage at the Princess’s, Portsmouth, with a gold dress ring by Mr. and Mrs. Charles Harrington as a mark of the success she has made of the part. After three years’ re-engagement she takes a short rest prior to rehearsing for pantomime at the Princess’s, Glasgow. ”

Nellie Shannon (1869–?) is, if anything, even more of an enigma than Amy Height. We are not even sure of her real name—in her one appearance in the England Census in 1901, she gives her name as “Ellen Shannon” (this census return is also the source of her year of birth). However, in a personal ad placed in the African American newspaper, the Freeman, in 1893, she gives the name of her mother as Jennie Sweet née Hall of Columbus, Ohio. At the same time, it is also probable that “Sweet” was not Shannon’s surname, either, as researchers have identified a likely candidate for the correct Jennie Sweet, and she did not marry her husband, Joseph Sweet, until 1876, 7 or so years after “Ellen” was born. In this regard, it is significant that the candidate Jennie Sweet had a son named “Benj Olmsted” living with her in 1900 who was born in 1861. It seems possible that Olmsted was also the surname with which Nellie Shannon was born. However, to date, no combination of these various names has resulted in any more biographical information on Nellie Shannon coming to light [61].

Illustrating what a small world the community of African American music hall artists was in late-Victorian England: Nellie Shannon, George Bohee, Amy Height and the second iteration of the Black Swan Trio all in the same production. Era, 15 May 1897. Public Domain.

Like Amy Height, Nellie Shannon made her first appearance on the English stage as a solo singer with her own variety act. This was in 1888, and she was billed as the “American coloured nightingale” [62]. This take on Jennie Lind’s billing as “the Swedish Nightingale” was in various forms applied to several African American soprano singers in this period in both the UK and the USA. Elizabeth Greenfield’s billing as the “Black Swan” was another take on this same billing. (As an aside: at least one reviewer commenting on Greenfield’s billing pointed out that, unlike nightingales, swans don’t sing [63].) At one time, Charles Hermann had two featured African American singers in his Uncle Tom’s Cabin company who were billed as the “Black Swan” and the “Black Nightingale” (Bessie Green and Bella Daniels, respectively) [64]. Corlene Cushman, who for most of her career was billed as the “Black Swan” in homage to (or imitation of) Greenfield, was even dubbed the “colored nightingale” in one review in an American newspaper [65].

It was, as stated above, in the summer of 1889, a year after her first known appearance in the halls, that Nellie Shannon was briefly a member of the Bohee Minstrel Troupe. Although I have written about this elsewhere, the story bears repeating here as it shows another aspect of the lives of black performers in England that speaks to why they performed caricatures of African American people created by white writers rather than versions that were true to their lived experiences.

Within one week of being hired, Shannon, who, it should be remembered, was all of 20 at the time, and another female artist with the Bohee troupe, Maria Ewing, were fired for breaking the strict rules that James Bohee, the troupe’s manager, had in place to govern the behaviour of members of the troupe both on stage and off. Aggrieved at their treatment, Shannon and Ewing took James Bohee to court for unfair dismissal and non-payment of wages (25s a week—at the time, roughly equivalent to the wages of a skilled tradesman; so a not inconsiderable sum). In court, George Bohee, appearing on behalf of his brother, stated that the two actresses had been seen drinking in a pub and out walking with a white man in direct contravention of the rules of the troupe that were posted in the dressing rooms for all the troupe’s artists to see. In reply, both Shannon and Ewing claimed not to have seen any such rules posted anywhere. The judge found for the Bohees, and in his judgement made plain that in his eyes, the real crime that the two actresses had committed was not breaking the troupe’s rules but crossing the colour line: “It was most desirable that these young women not be seen in public-houses or with white people at night” [66].

This whole affair is indicative of how precarious the situation of people of colour in England was in the period and to what degree the livelihoods of performers of colour depended on them conforming to the expectations of English society and, by extension, audiences. This is not to say, of course, that individuals of colour did not forge their own paths and find love across the colour line—as we have seen with both Bob Height and George Walmer—however, for the majority, earning a livelihood meant conforming to others’ norms.

Evidently undaunted by the setback represented by her sacking and the lost court case, Nellie Shannon returned to touring the halls as a solo performer—although now with “plantation songstress” added to her billing, suggesting that she was making use of the material she had learned during her brief time with the Bohees (Maria Ewing, in contrast, seemingly retired from the stage, although it is possible she simply changed her stage name). This period in Shannon’s career lasted from the summer of 1889 until the summer of 1891 when she joined the Charles Harrington company, then just beginning to tour the Stowe–Boucicault–Campbell triple bill around the halls. Her first role appears to have been as a performer in the plantation festival scene in a performance of “The Octoroon” in June 1891. However, within a few weeks, she had also debuted as Topsy in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a role she would play first for Harrington and then for other producers—including both Charles Hermann and W T Rushbury—for the next 16 years [67].

During her time performing in Tom shows for various producers, Nellie Shannon would act alongside many of the other performers we have already met. In the Harrington company, she would, at different times, act alongside George and Cassie Walmer, Bentick Rowe, and, somewhat ironically, George Bohee, who became a featured musician in plantation festival interludes following the death of his brother in 1897 and the subsequent dissolution of the minstrel troupe that they ran together. She would also appear alongside another of her old associates from her brief spell with the Bohee brothers, as she and Amy Height both worked for Rushbury in the 1906–1907 season. Beyond the world of the Tom shows, she, like Amy Height, was a regular in Christmas pantomimes—including Robinson Crusoe [68].

As the above shows, Shannon was another artist of colour who, thanks in no small part to the popularity of Tom shows, had a long and diverse career in the English halls. It is frustrating to have to report then, that, aged 38, after an appearance in a Rushbury production in the summer of 1907 (in the Shetland Isles) [69], she simply vanishes from the records. Without a real surname for her, it has to date proved impossible to determine what happened to her.

Part II: Cuckoos

“Miss Nellie Christie (Abdallah) rendered her songs charmingly and won repeated encores for a curious castanet accompaniment to one of them. ”

No discussion of Tom shows would be complete without mention of the white artists in blackface who starred in them alongside artists of genuine African heritage, particularly those artists, like Nellie Christie, who became known primarily for blackface roles. As I will demonstrate, there was often an element of reluctance on the behalf of the artist, a sense of taking this route because it was the only thing they tried that went over (i.e., that the audience responded positively to); that they, like artists of genuine African heritage, were in a sense also caught in their orbit. At the same time, I will show that performing in blackface was always still a choice, a choice that some white artists chose not to make.

Like “Nellie Shannon”, “Nellie Christie” was also a stage name. However, thanks to her marriage to celebrated scenic artist James A Hicks, we know that Nellie Christie’s real name was Jessie Heaver (1860–1940) and she was born in Hammersmith, London, the daughter of a carpenter [71]. She got her start in the halls in pantomime, initially for actress–producer Kate Fellowes [72], playing chambermaids and other small roles before finding success as a principal boy (the male romantic lead—in a traditional pantomime, a role played by an actress is male attire [73]). She quickly came to specialise in “trouser roles”.

In the 1884 Christmas season, Christie played the part of the chief of the pirates in a production of Robinson Crusoe that predated Geoffrey Thorne’s addition of the character of Topsy to the piece. However, as the decade progressed, although still only in her twenties, the sorts of roles she was being offered tended to be that of older men and women. It is telling in this regard that, in a review of the play “The Two Orphans” (Les deux ophelines), in which Christie played the “old hag” La Frochard, the critic for the Stage wrote “We are pleased to note this clever actress accepting our suggestion to “go in” for parts of this temperament; her abilities certainly tend this way”. This was a reference to a comment made by the same critic two weeks earlier to the effect that Christie would “do well to devote her talents to character parts”. Jumping ahead to 1892, in a review of Christie’s performance of Topsy in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a critic for the Pall Mall Gazette wrote that “the generosity of nature has prevented Miss Nellie Christie from looking like the young girl slave, and her art makes no amends”, while in The People, another critic was even blunter, writing, “the sole objection being that there was too much of her—not for the audience, but the character bodily” [74].

Nellie Christie on the cover of the sheet music to her song “Chloe”, 1894. Author’s own collection.

Christie’s body shape, as contemporary images confirm, did not conform to that expected of actresses playing leading parts, particularly youthful leading parts. This came to define her in the eyes of critics and audiences. There was praise a-plenty for her skills as an actress, but only when she played parts that audiences considered her physically suited.

In 1889, Christie played her first blackface role, that of Daphne, “an octoroon”, in a production of “The White Slave” [75], the Tom show staple; however, this was just one of several roles she played that year and the only one in blackface. This would continue to be the case for the next few years, but that would change once she played Topsy for Hermann in 1892. Although she only lasted one month in the part—the reviews were as we have seen not kind—it resulted in her adding blackface minstrelsy to her CV. Thus, the following year, she played Bella a “coloured maid” in “Fun on the Bristol”, a part that included several minstrel songs. She returned to the role the following year, and one of the minstrel songs she sang in this second staging, “Chloe”, became a “breakout hit” [76].

On the back of the success of “Chloe”, Christie embarked on a new career to supplement her continuing appearances in pantomime, touring the halls as a solo variety act—a solo blackface variety act; one contemporary reviewer even credited her with being the first female solo variety artist to wear blackface (as distinct from the many female blackface performers in Tom show ensembles). Her success in this new role was cemented when to supplement the material she had brought over from “Fun on the Bristol”, she added an impersonation of Eugene Stratton, the leading (in London at least) male blackface minstrel of the day [77]. One of Stratton’s hit songs was called “Susie Tusie”, and Christie began to bill herself as “the real Susie Tusie” and the “female Eugene Stratton” [78]. Name recognition went a long way with booking agents who had hundreds of acts of any given type to pick from; Christie’s bookings increased. And when it came time to pick a role for the 1894 Christmas pantomime season, she chose to build on that success by playing another blackface role: Topsy in Robinson Crusoe—the role that Amy Height had originated a decade earlier [79].

Whether through accident or design, by 1895, Christie had become primarily a blackface performer. She was described in the theatrical press as a “negro comedienne”, “black vocalist”, “plantation songstress”, and singer of “negro songs”. She would keep the “real Susie Tusie” billing for at least the next ten years and would go on to play pantomime versions of Topsy in not only Robinson Crusoe but other pantomimes (Cinderella, Babes in the Woods) every Christmas for as long (by which time, she was well into her forties). She became so well-known in the role that she even engaged in self-satire—appearing as “Queen Susantusan, Empress of Morocco” in a production of Dick Whittington [80].

Era, 29 September 1894. Public Domain.

Finally, and to bring things in a sense full circle, in as acute a commentary of the struggles of genuine performers of colour performing to audiences used to white performers in blackface as it is possible to imagine, seven years after critics had praised Nellie Shannon for her naturalism and derided Nellie Christie for her artifice in their relative performances as Topsy in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a critic reviewing an 1899 performance by Shannon in the role wondered if she had based her costume on that of Christie in her pantomime version of the character [81]. To artifice belonged the final victory.

“The Renshaws “eccentric musical mimics” are clever and amusing. On the banjo, Russian bells, and “bones” they are equally good, but it is with their performance on the American castanets that they hit the public fancy, the rendering of the “Anvil Chorus” from “Il Trovatore” on those peculiar instruments being very effective.”

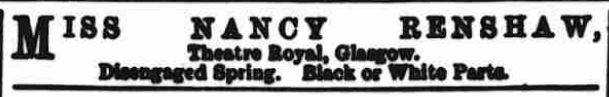

To consider how usual or unusual was the career trajectory of Nellie Christie, it is worth briefly considering that of a female blackface performer who was her contemporary, Nancy Renshaw. Nancy Renshaw started her career in the early 1890s as one half of a musical act called the “Dandy Renshaws, grotesque musical mimics” and was at this early stage in her career, primarily known as a “bone soloist”—a player of the bones, the castanets-like percussion instruments synonymous with blackface minstrelsy but not, it must be made clear, found only in blackface minstrelsy—the Renshaws were not a blackface act.

The Renshaws were a fixture of the variety troupe that accompanied “Hamilton’s Excursions” (presentations of historical events and travelogues in the form of large painted screens) for several years, but, following the illness (and death?) of her partner “J Renshaw” in 1896, Nancy Renshaw struck out alone as a “vocalist and bone soloist” [83]. More significantly, she also started to appear in character in pantomimes (including, like Christie, as a principal boy). And it was with this development, and undoubtedly due to the connection in the minds of English audiences between the bones and blackface minstrelsy, that Renshaw started to appear in blackface— including as one of the enslaved African characters in a production of the Tom shows staple “The Octoroon” [84].

Era, 15 February 1902. Public Domain.

As with Christie, from there, it was a case of, the more success that Renshaw had performing in blackface, the more she made it a feature of her stage persona. This can be tracked by looking at the changing way she described herself in advertisements and notices from 1896, when she first went solo, until 1904, when her stage persona was fully realised: ‘Vocalist and Bone Soloist’ (1896) “Chambermaid, Boys and Speciality” (1898) “Negress and Specialty” (1899), “Black or White Parts” (1902), “Negro Comedienne and Bone Soloist” (1904). Like Christie, she continued performing blackface roles and variety into the second decade of the Twentieth Century [85].

It is clear that with both these performers, their journeys toward becoming primarily blackface performers began with circumstances largely beyond their control (for Christie, a narrowing of available parts due to not conforming to prevailing standards of female beauty; for Renshaw, losing her performing partner and being a player of an instrument synonymous with blackface minstrelsy) and in a real sense, they embraced blackface simply because this, amongst the different things they tried, is what “went over” with their audiences. Later performers, like May Henderson, looking to the success of Christie and Renshaw, would take a more direct route to blackface [86].

Although I know of no testimony that either Christie or Renshaw might have left behind that might tell us what they thought about this, I think we can draw on the experience of another blackface performer to hazard a guess. Eugene Stratton—the successful male blackface minstrel whose act Nellie Christie pastiched to great success—had, famously, shortly after his first great solo success in blackface, tried to return to performing a “conventional” variety act, only to be given the cold shoulder by audiences. Bowing to what he regarded as the inevitable, Stratton returned—reluctantly—to performing in blackface [87].

It seems safe to assume, even if only because it limited them as performers, Christie and Renshaw would rather not have become known primarily as blackface performers. At the same time, we should also say that this was a choice. Yes, not making this choice—as Stratton discovered—might have hurt their careers, at least in the short term; however, we can point to at least one artist who chose not to become a blackface performer despite this route being open to them.

Eugene Stratton out of blackface. Author’s own collection

“Miss Winifred Johnson, the highly accomplished American banjoist, is on her way to London, having started on board the s.s. “Alaska” on May 30. This young lady, who has been christened “the world’s greatest banjo expert” will shortly be seen and heard in the halls.”

Winifred Johnson (1865–1931), the American actress, dancer, and banjo virtuosa, settled in England in 1891 with her husband, the Canadian-born American comedian R G Knowles. The couple were great friends of Eugene Stratton, with whom R G Knowles played baseball in the London league that Knowles founded [89]. Higher up the bill than her husband when she married him—as might be guessed from the above quote that mentions her imminent arrival in the UK but not his—Johnson was the daughter of actor W T Johnson and had got her start as an infant actor, playing little Eva in Tom shows, a role she would continue to play well into adolescence, and which would prove crucial to the genesis of her variety act as an adult. After retiring from the stage while still a teenager, she went to school in New York. There, she followed the fashion of the moment and learned the banjo. She was forced to return to the stage following the early death of her father, as a song and dance variety artist; however, over time, it was her banjo playing that became the principal draw [90].

Winifred Johnson, Sketch, 28 November 1894. Author’s own collection.

Although Johnson’s act included a segment described by one critic as imitating “a negress singing a plantation melody” [91], and these days, we would probably call it “cultural appropriation”, it was not blackface minstrelsy; it was rather, Johnson’s attempt to reproduce the back-stage performances by people of colour that she had witnessed for herself in her youth during her time with the Tom shows. To be clear: Johnson’s act was not and could never be authentic—she was not African American; however, she strived for what she and her audiences would regard as authenticity, particularly in her dancing, citing direct observation of African American dancers as her inspiration. Critically, she did all of this without donning blackface makeup.

Blackface was a choice, and it was a choice that Johnson chose not to make.

Epilogue: Oiseaux de Nuit

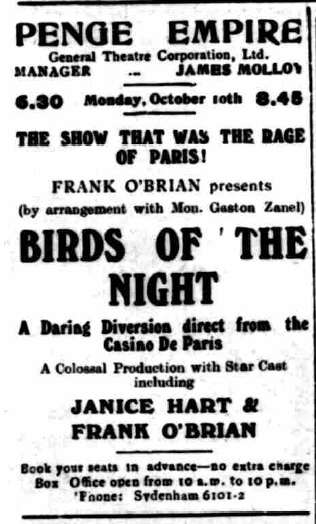

“Frank O’Brian presents JANICE HART in Josephine Baker’s Parisian Success:— “BIRDS OF THE NIGHT” (Les Oiseaux de Nuit) !The Most Colossal Production on Tour! ”

Tom Finglass and Gay Perse (Gracie Finglass). A Twentieth-Century blackface minstrel, Finglass would go on to play the performer who inspired him, Eugene Stratton, in a 1940 film about the Nineteenth-Century Music Hall (You Will Remember).

Blackface minstrelsy survived well into the second half of the Twentieth Century, killed ultimately only by the rise of the civil rights movement [93]. However, Tom shows had died a natural death long before this, and it was changes in musical tastes, not sensitivity to their depictions of people of colour, that finished them. By the turn of the Twentieth Century, the inherently rural, folksy sound of the “plantation festivals” had been supplanted in the popular affection by the syncopated rhythms of ragtime, which would, within a decade, itself be supplanted by jazz. Although a white man called Whiteman would dub himself “the King of Jazz”, performers and composers of colour achieved far more agency in the creation and curation of these two genres of music and would play a far greater role in the creation of stage shows centred on them, leading to a centering in turn of the lived experience of African Americans.

This is not to say that the earliest of these shows was free from the pervading influence of the Tom shows. In 1903, the African American blackface minstrels Bert Williams and George Walker premiered “In Dahomey”, a show created and performed by African Americans and toured around the world. In their show, Williams and Walker subverted the “dandy” and “coon” characters of the blackface minstrel shows to satirical effect. However, as with all satire, it is not clear to what degree their audiences were laughing with them or at them, particularly when those audiences were white. Indeed, “plantation humour” remained a staple of pioneering shows of the 1920s like “Shuffle Along”, “Plantation Revue”, and “Blackbirds” [94].

Arguably, then, it is only with the success in Europe of Josephine Baker, who had appeared as a chorus girl in “Shuffle Along”, that a true break with the past was made—although this development was not without its own controversies and detractors, including from within the African American community [95]. La Revue nègre, the first Baker star vehicle, opened in Paris in 1925. Despite featuring African American performers and musicians, including Sydney Brechet, recruited directly from America, the show was created specifically for the Paris stage and owed more to the revues staged in the African American-owned clubs of the Montmartre district than it did to its Broadway predecessors. Indeed, many of the musicians, Brechet included, had already performed in those same clubs in the years following the end of the First World War. Baker’s next Parisian project La Folie de jour at the Folies Bergère, in which she performed the danse sauvage in little more than a skirt made from 16 bananas, made her a star [96].

Over in London, Cassie Walmer and her new professional partner, and future second husband, Frank O’Brian were taking note.

Cassie Walmer. Era, 15 November 1916. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Walmer worked steadily after re-debuting as a child performer in 1897 following the death of her father, George Walmer, including tours of Australia and New Zealand. In the early part of her solo career, she was billed as the “Black Princess” and her act owed much to those of her predecessors like Amy Height and Nellie Shannon and the expectations of English audiences, consisting principally of “plantation melodies”. As she matured as an artist—and musical tastes changed—she began to incorporate ragtime-infused buck, wing, and sand dancing and was billed as a “contralto, comedienne, and eccentric dancer”; however, as late as 1909, she was still being described in the press by the old blackface minstrel label of “coon delineator” [97].

The real change in her career came after the end of the First World War when she partnered with North-East England comedian and actor Frank O’Brian. She adopted a new stage name “Janice Hart”, making use of it at first sporadically (it makes a brief appearance in 1919 and then is not seen again until 1922), then in parallel with Cassie Walmer, before, finally, in the mid-1920s, switching to using it exclusively. It has been suggested that this decision to use the Janice Hart stage name exclusively was motivated by the rise to fame of Josephine Baker and the coincidental similarity in the two names. (It has also been written that the name “intentionally evoked the popular French performer, Josephine Baker”, but this could not be the origin of the stage name, as Baker was unknown in 1919, when Walmer first used the Hart stage name, and did not become famous until 1926, two years after Walmer switched to using the Hart stage name permanently.) [98]

Whatever the real motivation behind the permanent switch to the Janice Hart stage name, it is clear that this was accompanied by a permanent switch in the type of act that Walmer performed, as the Hart–O’Brian combination became known for increasingly elaborate and expensively costumed musical revues in the Baker vein. That this link was deliberate is clear from the quote above, which shows the pair making the almost certainly entirely spurious claim that their 1931 revue “Birds of the Night” was adapted with permission from a Baker original. (In adverts, the production was said to be “Direct from the Casino de Paris” and “by arrangement with Mon. Gaston Zanel”, but the name of the revue that Baker was starring in at the Casino de Paris was Paris qui remue, and Gaston Zanel was Baker’s couturier not producer.) [99]

Sydenham, Forest Hill, and Penge Gazette, 7 October 1932. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

False advertising aside, gone at last was any link to blackface minstrelsy and the Tom shows.

Jamie Barras, April 2025

Notes

Copy for an ad for the Theatre Royal, Weymouth, Southern Times and Dorset County Herald, 16 July 1892.

David Pilgrim, ‘The Tom Caricature’, https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/tom/homepage.htm, accessed April 2025.

This was in London in 1878, the production was the version produced by Jarrett and Palmer, and the two theatres were the Princess’s and the Royal Aquarium (the former on Oxford Street, the latter just north of Parliament Square), ‘Theatres: The Princess’s and the Aquarium’, Illustrated London News, 7 September 1878.

For example, in October, the Harrington production was in Edinburgh (‘Amusements in Edinburgh: Theatre Royal’, Era, 1 October 1982) while the Hermann production was in London (ad, Princess’s Theatre, Daily Chronicle (London), 25 October 1892).

Shannon review: ‘The Grand’, Era, 30 July 1892; Christie Review: ‘The Princess’s Theatre’, Morning Post, 31 October 1892.

Places of birth for Shannon and Christie taken from censuses and other information presented in the text.

Hazel Waters, ‘Putting on ‘Uncle Tom’ on the Victorian Stage’. Race & Class, 2001, 42(3), 29-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396801423002 (Original work published 2001).

The plot of the Fitzball version is described in an 1852 review: ‘Olympic’, llustrated London News, 25 September 1852.

The term “Ethiopian Opera” comes to represent specifically minstrel performances that claim to present scenes of plantation life only after the first stage versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin appear, and it can be argued that these productions are inspired by the latter, not the other way around. See, for example, ad for Liverpool Queen’s Hall, Northern Daily Times, 2 September 1854 (two years after the first Uncle Tom’s Cabin plays are staged). However, the term “Ethiopian opera” as a descriptive term for blackface minstrel performances predates this, and, indeed, the term is used in this way in a review of a satire of Uncle Tom’s Cabin “Uncle Tom’s Crib” in 1852: “Here, where Ethiopian opera has had such undeniable success, a smart trifle has been given, under the title of ‘Uncle Tom’s Crib’” (‘Strand’, Lady’s Newspaper, 25 Otober 1852).

‘Ethiopian Serenaders’, Lloyd’s Weekly London News, 24 January 1843.

Lew Dockstader, ‘History of Minstrelsy: Its Rise and Decline Since 1843 and Its Triumphant Renaissance.’, Washington Post (D.C.), 12 October 1902. Virginia Minstrels illustration: Music Division, The New York Public Library. "The celebrated negro melodies as sung by the Virginia Minstrels, adapted for the piano forte by Thos. Comer" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed April 20, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1915ede0-c5a8-012f-f6b2-58d385a7bc34.

Robert E McDowell, “Bones and the Man Toward a History of Bones Playing. Journal of American Culture”, 1982, 5: 38-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-734X.1982.0501_38.x, accessed 7 April 2025.

University of Toronto Juba Project led by Professor Emeritus Stephen Johnson, https://thejubaproject.wordpress.com/featured-performers-documents/juba-and-the-ethiopian-serenaders-in-the-uk-1842-52/, accessed 4 April 2025.

David Taylor, ‘From Mummers to Madness’, Chapter 12 ‘The Minstrels Parade: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Music Halls’, University of Huddersfield Press, 2021. Available to download here: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/50575, accessed 20 January 2025.

David Pilgrim, ‘The Coon Caricature’ https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/coon/homepage.htm, accessed April 2025. See also Note 12 above.

‘The Court’, Wells Journal, 13 May 1854.

https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-rivers-and-the-black-swan, accessed 5 April 2025.

‘The Jubilee Singers’, Reading Observer, 11 April 1874.

See Note 17 above.

“Despite the success of William H Lane, a genuine coloured comedian known as Juba, who made a sensational London appearance in 1850, later authentic negro acts were rejected by the British public as lacking polish and refinement”, Barry Anthony, ‘Early Nigger Minstrel Acts in Britain’, Music Hall, Issue 12.

Alabama Minstrels “From 44 Broadway, New York”: ad, Paisley Herald, 11 January 1865. This being the address of Fellow’s Opera House, home of the Christy Minstrels: https://www.musicals101.com/bwaypast2.htm, accessed 6 April 2025.

John Johnson and James Lewis of the Alabama Minstrels were from New York; other members whose identities we can trace were from Canada (Charles Hagerman) and Philadelphia (John Waters): 1861 England Census, St Martins in the Fields district, entries for the above-named men, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 8 April 2025.

The names of the members of the Alabama Minstrels are contained in advertisements for the troupes in the English press, for example, Note 19 above, Era, 3 January 1866, Loughborough Monitor,1 March 1866, and Falkirk Herald, 14 February 1867. Biographical details for George Hagerman are drawn from the 1861 England Census entry for George Hagerman, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 6 April 2025.

“Japanese Tommy”: Josephine Lee, “Blackface Minstrelsy’s Japanese Turns.” In Oriental, Black, and White: The Formation of Racial Habits in American Theater, 60–78. University of North Carolina Press, 2022. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469669632_lee.8, accessed 6 April 2025. Bob Height, with Hague: ad, London Daily Post, 5 November 1873.

This account of the career of the Georgia Minstrels is drawn from: Eileen Southern, ‘The Georgia Minstrels: The Early Years’, Inter-American Music Review, 2019, 10, 157–167. https://iamr.uchile.cl/index.php/IAMR/article/view/53523, accessed 6 April 2025.

‘Theatres: Princess’s and the Aquarium’, Illustrated London News, 7 September 1878.

Kurt Gänzl, The Black Crook, entry, The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre (New York: Schirmer Books, 2001); reproduced here: https://kurtofgerolstein.blogspot.com/2016/10/the-black-crook-real-story-of.html, accessed 7 April 2025.

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin at Manchester”, Era, 25 September 1878.

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, Western Daily Press, 15 August 1878.

The names of some of the performers and their combinations can be found in advertisements and reviews of the London production, for example, ad for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Globe, 19 August 1878, and the touring company, for example, ad, Birmingham Daily Mail, 12 September 1878. To these can be added the surnames of the performers in the combinations, which can be found in ads for the New York production, for example, Narragansett herald (Narragansett Pier, R.I.), 9 March 1878. That the speaking parts were played by white actors can be reconstructed from reviews, for example, Marie Bates, who played Topsy is London is described in one review as a “white actor with a blackened face”, Scrutator, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, Truth, 19 September 1878; while Alfy Chippendale, who played Topsy in the touring company, is described in another as “a white young lady”, see Note 25 above.

Ad for the Corn Exchange, Stirling, Stirling Observer, 14 June 1879.

‘Death of Harry Palmer’, Sun (New York, NY), 21 Jul 1879; new productions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin: see Note 30 above.

John A. Degen, “How to End ‘The Octoroon.’” Educational Theatre Journal, 1975, 27, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/3206111.

“The White Slave”: Diana R. Paulin, “Performing Miscegenation: Rescuing The White Slave from the Threat of Interracial Desire”. Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, 1998, 13, 71-86. https://journals.ku.edu/jdtc/article/view/1998, accessed 10 April 2025. For an example of a week of performances that comprises all three plays, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Octoroon, and The White Slave, see Note 4, first reference.

“Bloodhounds on the Stage”, Manchester Evening News, 30 November 1883. The dogs were variably described as “American mastiffs” and “South American bloodhounds” in the press. The dog that carried out the attack that led to the court case was called “Clingo”; by the time that he died in 1886, he had cost Hermann £300 in fines: ‘Epitome of News’, West Sussex County Times, 25 September 1886.

The dog attack and Bill Edwards and Bentick Rowe (named here as ‘Edwards’ and ‘Ben Row’, respectively) ‘A Realistic Performance’, Evening News (Portsmouth), 4 May 1883. Bill Edwards ‘the original coloured Uncle Tom’: ad, Corn Exchange, Derby, Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal,18 January 1884. Bentick Rowe as Uncle Tom at the turn of the century: ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’, Gloucestershire Echo, 9 June 1903.

Edwards was stll playing the role as late as 1899: Morning Leader, 21 August 1899. Billing as “the only original coloured Uncle Tom” at the head of his own company: ad, ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’, Essex Newsman, 20 August 1892.

ad for City Hall, Brechin, Brechin Advertiser, 10 December 1889.

R B Lewis with Harrington: ‘Salford: Theatre Royal’, Era, 22 May 1886; Lewis with Rushbury: ad for the Assembly Hall, Montrose, Montrose Review, 14 January 1887; Lewis taking over Rushbury’s company: ‘Dumbarton’, Lennox Herald, 6 October 1888; R. B. Lewis’s American, etc.: see Note 36 above.

Matthew W Wittmann, ‘Empire of Culture: U.S. Entertainers and the Making of the Pacific Circuit, 1850–1890’, PhD Thesis, University of Michigan, 2010, 253 (footnote), 267–268. R B Lewis as Uncle Tom in New Zealand: ‘Amusements’, Hawkes Bay Herald, 14 March 1882.

Lewis as Othello: ad, Stage, 30 August 1889. Lewis as Constable Bullock in East Lynne: ‘Galway’, Era, 5 November 1892.

This information can be construed from the marriage announcement of Arthur Warren and Lena L Lewis “daughter of the late Mr R B Lewis”, Stage, 22 July 1897.

Lena Lewis playing Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin: see, for example, ‘Amusements in Edinburgh’, Era, 6 April 1889. For her marriage, see Note 40 above. There was at least one other “Miss Lena Lewis” active in this period, appearing, for example, as Cinderella in 1888: ‘Dover, Town Hall’, Stage, 30 November 1888. This would appear to be too mature a role for the child we know R B Lewis’ daughter to be (8 years old).

The earliest mention of Geroge Walmer in the role of Uncle Tom that I have found is: ‘Theatre Royal, Cheltenham’, Cheltenham Mercury, 15 March 1887. The last, almost exactly a decade later, accompanies the announcement of his death and burial: ‘General Summary’, Exeter Flying Post, 31 March 1897. He died on stage while performing the role that had, if not made him famous, at least provided him and his family with a livelihood. His age at death can be found on his death certificate, registered 27 March 1897, Dudley District, certified copy obtained from the General Registry Office, April 2025. “Horrors of South American slavery”: ‘Theatre Royal–Uncle Tom’s Cabin’, Scotsman, 18 August 1891. George Walmer “a black” was fined 10s for disorderly conduct in Nottingham in 1875: Nottingham Journal, 17 April 1875; there was a George Walmer, “pianoforte player”, US born, on the Isle of Man at the time of the 1881 Census: 1881 Isle of Man Census return for Maughold, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 16 April 2025.

Stephen Bourne, “Walmer, Cassandra [Cassie] [also known as Janice Hart] (1888–1980), music-hall entertainer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 12 Oct. 2023; Accessed 12 Apr. 2025. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-90000380682.

‘Violation of the Public Amusements Act at the Theatre Royal’, Blyth News, 23 January 1892; ‘Children on the Stage’, Manchester Courier, 28 December 1895.

Sylvia Stella as little Eva: ‘Theatre Royal’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 6 December 1892; as Topsy: ‘Miss Sylvia Stella’, Bristol Magpie, 5 January 1905; marriage to her cousin: ‘Births, Marriages, Deaths’, Era, 3 May 1913 (the notice, somewhat bizarrely, makes an oblique reference to the familial relationship by separately listing John Baptist Zerbini as a grandparent for both). Henry Halfpenny was the son of Zerlina Zerbini’s sister, Violetta. The details of Charles Harrington and Zerlina Zerbini’s lives and career are taken from their obituaries: Charles Harrington: Stage, 8 December 1932; Zerlina Zerbini: Stage, 27 July 1933.

‘Grand Theatre, Islington’, Sporting Life, 30 December 1886.

Synopsis of Geoffrey Thorne’s dramatisation of Robinson Crusoe taken from a review of the first production, ‘Grand’, Daily Chronicle (Liverpool), 28 December 1886.

Variety bills and ‘Octoroon Songstress’: ‘Oddfellows’ Music Hall, Keighley’, Magnet (Leeds), 8 September 1883. Pantomime, see, for example, Note 44 above; minstrel shows, see, for example, ‘Royal Assembly Rooms, Reading: Bohee Operatic Minstrels’, Reading Observer, 21 September 1889; Tom shows, see, for example, ‘The King’s, Hammersmith’, Era, 27 June 1903.

‘Aberdeen: People’s Palace’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 5 April 1895.

See Note 17 above.

Amy Height can be found in the 1891 England Census (age 30, place of birth New York), 1911 England Census (aged 29, place of birth Boston), and 1901 Wales Census (age 30, place of birth America). Her place of birth is given as Boston in a review of her perfomance in “Madame Delphine” in the San Francisco call (San Francisco, CA), 22 July 1900. She is said to be English-born in a report (written by an African American music hall performer who was visiting England) in the Freeman (Indianapolis, Ind.), 14 September 1901, and decribed as being English and never having been to America by Al Dale, ‘Dale at the London ‘Alls’, New York journal (New York, NY), 13 July 1897. This was information given to Dale by someone he asked about Height.

‘Alhambra, Hull’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 23 December 1892.

Robert Height, widower: marriage register for Robert Henry Height and Mary Abbot, Everton, 21 June 1874, Liverpool, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1930, ancestry.co.uk, Ancetry.com Inc., accessed 14 April 2025.

See Note 48 above, first reference.

Robert and Mary Height, in Edinburgh, 1881 Scotland Census, scotlandspeople.gov.uk, accessed 14 April 2025.

See Note 17 above.

Amy Height’s first and last recorded appearance with the Bohee Brothers are 21 July 1888 and 18 July 1890: ‘The Bohee Brothers’, Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 21 July 1888; ‘Croydon–Royal’, Stage, July 1890.

‘Provincial Productions’, Stage, 2 November 1899.

‘Ellen Shannon’: Everton district, 1901 England Census. Nellie Shannon was preparing to appear in Birkenhead at the time of the census, supporting the supposition that “Ellen Shannon” is Nellie Shannon: ‘Birkenhead—Royal’, Stage, 11 April 1901. Personal ad trying to trace her mother: ‘Lost Relatives’ Column, Freeman (Indianapolis, Ind.), 4 February 1893; Jennie Sweet candidate: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1742174752762741/posts/3578630589117139/, accessed 14 April 2025; ‘Jennie Sweet’, ‘Joseph Sweet’, and ‘Benj Olmsted’: Columbus, Ohio District, 1900 US Federal Census, ancestry.co.uk. Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 4 April 2025.

‘American Coloured Nightingale’: ad, Crown Music Hall, Derby Daily Telegraph, 28 March 1888.

‘The ‘Black Swan’’, Montrose Review, 23 December 1853.

Ad for the Theatre Royal, York, Yorkshire Gazette, 24 November 1883.

‘The Minstrel Festival Tonight’, Wheeling daily inteligencer (Wheeling, WV), 22 January 1884.

‘A Banjoist in Court’, Era, 20 July 1889; ‘Coloured Artists and Their Conduct’, Guardian (Newcastle), 20 July 1889.

‘Plantation Songstress’: ‘Artists at Liberty–Ladies’, Magnet (Leeds), 31 August 1889; in “The Octoroon” for Harrington: ad for Theatre Royal, Leigh, Leigh Chronicle, 12 June 1891; in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” for Harrington: ‘Theatre Royal–Uncle Tom’s Cabin’, Scotsman, 18 August 1891; for Hermann: ‘Glasgow–Grand’, Era, 19 May 1906; for Rushbury: ‘Galashiels’, Era, 20 September 1906.

Nellie Shannon acting alongside George and Cassie Walmer: ‘Dinner to Poor Children at North Shields’, Shields Daily Gazette, 26 December 1891, and ‘Theatre Royal, North Shields’, Shields Daily Gazette, 28 December 1891; alongside George Bohee and Bentick Rowe: ‘Newcastle Upon Tyne–Grand Theatre’, Era, 21 May 1898; alongside Amy Height: ‘The Octoroon’, Linlithgowshire Gazette, 11 January 1907. In Robinson Crusoe: ad for Broadway Theatre S.E., Kentish Mercury, 21 December 1900.